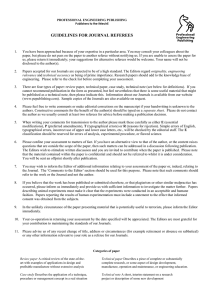

Writing for Scholarly Journals

advertisement