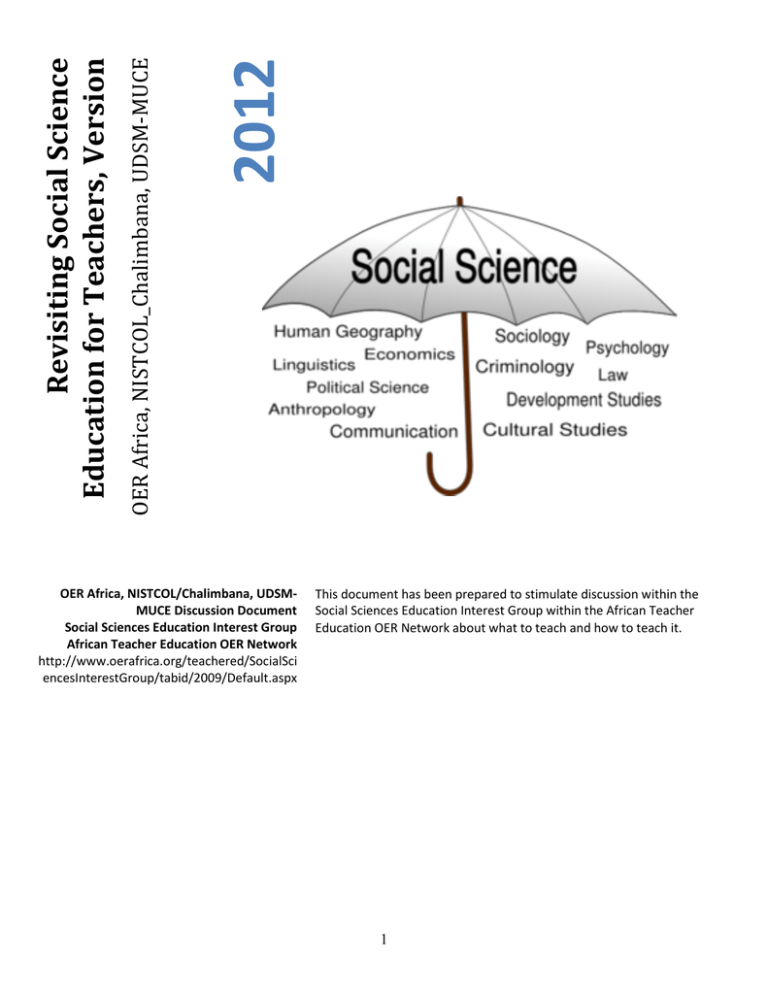

Revisiting Social Science Education for Teachers, Version 1.0

advertisement