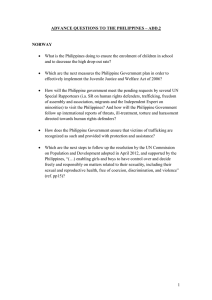

Analysis of Specific Legal and Trade-related Issues in a Possible PH

advertisement