Nonrefundable Retainers - The Fordham Law Archive of

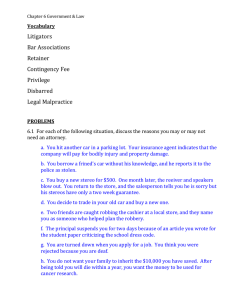

advertisement