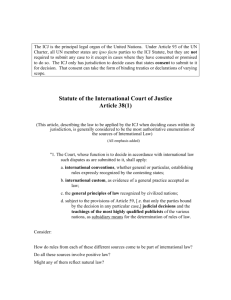

The attribution of international responsibility to a State for

advertisement