Econ 101: Principles of Microeconomics - Chapter 12

advertisement

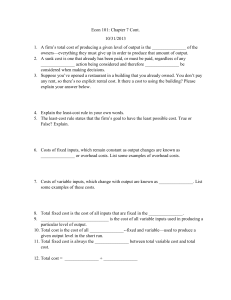

Econ 101: Principles of Microeconomics Chapter 12 - Behind the Supply Curve - Inputs and Costs Fall 2010 Herriges (ISU) Ch. 12 Behind the Supply Curve Fall 2010 1 / 30 Fall 2010 2 / 30 Outline 1 The Production Function 2 Marginal Cost and Average Cost 3 Short-Run versus Long-Run Costs Herriges (ISU) Ch. 12 Behind the Supply Curve Overview In this chapter we turn our attention to the firm. A firm is an organization that produces goods or services for sale. We will begin by characterizing the relationship between the firm’s inputs and the quantity of outputs it produces. The production function describes the relationship between the quantity of inputs and the quantity of outputs that the firm produces. Basic characteristics of the production function has implications for the cost structure for the firm, which in turn has implications for the firm’ ultimate supply function. Herriges (ISU) Ch. 12 Behind the Supply Curve Fall 2010 3 / 30 The Production Function The Short Run and the Long Run It is useful to categorize firms’ decisions into - Long-run decisions–involves a time horizon long enough for a firm to vary all of its inputs - Short-run decisions–involves any time horizon over which at least one of the firm’s inputs cannot be varied To guide the firm over the next several years, manager must use the long-run view To determine what the firm should do next week, the short run view is best. Herriges (ISU) Ch. 12 Behind the Supply Curve Fall 2010 4 / 30 The Production Function Production in the Short Run In the short-run, the firm’s inputs can be divided into one of two categories 1 Fixed inputs - These are inputs whose quantity is constant for some period of time (regardless of how much output is produced). - Typically, fixed inputs will include land and machinery, though they can also include certain types of labor (due to contracts). 2 Variable inputs - These are inputs whose quantity the firm can vary, even in the short run. - Examples of variable inputs often include labor, energy, fuel, etc. When firms make short-run decisions, there is nothing they can do about their fixed inputs; i.e., they are stuck with whatever quantity they have. However, they can make choices about their variable inputs. Herriges (ISU) Ch. 12 Behind the Supply Curve Fall 2010 5 / 30 The Production Function Total Product To fix ideas, suppose we have a firm whose only variable input is labor All other inputs (capital, land, raw materials, etc.) we will assume for now are fixed. Total product is the maximum quantity of output that can be produced from a given combination of inputs. The total product curve shows how the quantity of output depends on the quantity of variable input, for a given quantity of the fixed input. We would generally expect the total product curve to be increasing; i.e., as the quantity of the variable input increases, we would expect total output to increase. Herriges (ISU) Ch. 12 Behind the Supply Curve Fall 2010 6 / 30 The Production Function Consider John’s Woodworking Shop Again Units of Labor 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Herriges (ISU) Total Product 0 10 35 80 160 193 218 239 257 Ch. 12 Behind the Supply Curve Fall 2010 7 / 30 Fall 2010 8 / 30 The Production Function The Total Product Curve Herriges (ISU) Ch. 12 Behind the Supply Curve The Production Function Marginal Product Notice that the Total Product curve is always increasing in this case, but that it’s slope is not the same throughout. - Initial the slope is increasing - but eventually it starts to flatten out. The slope of the Total Product Curve is the Marginal Product of labor. Formally, Marginal Product of Labor (MPL) = = Change in Quantity of Output Change in Quantity of Labor ∆Q ∆L Tells us the rise in output produced when one more worker is hired Herriges (ISU) Ch. 12 Behind the Supply Curve Fall 2010 9 / 30 The Production Function Units of Labor 0 Total Product 0 Marginal Product 10 1 10 25 2 35 45 3 80 80 4 160 33 5 193 25 6 218 21 7 239 18 8 Herriges (ISU) 257 Ch. 12 Behind the Supply Curve Fall 2010 10 / 30 The Production Function The Marginal Product Curve Herriges (ISU) Ch. 12 Behind the Supply Curve Fall 2010 11 / 30 The Production Function Marginal Returns To Labor As more and more workers are hired, the MPL is at first increasing - This is known as increasing returns to labor - This is typically due to the returns to specialization - It can also arise due to minimum labor requirements for equipment. Eventually, however, the MPL starts to decline - This is known as diminishing returns to labor - This arises as the gains from specialization are exhausted and - The constraints caused by the fixed inputs start to bind This pattern of MPL (and for other inputs) is thought to hold for most industries. Consider the problem of a woodworking shop. Herriges (ISU) Ch. 12 Behind the Supply Curve Fall 2010 12 / 30 Marginal Cost and Average Cost Production and Firm Costs Understanding the nature of a firm’s production function is important in that it has implications for the firm’s costs. In the short run, the firm’s costs can be divided into two broad categories: 1 Total Fixed costs (TFC): These are costs that do not depend upon the quantity of output produced. - These costs are typically associated with fixed inputs. - Examples of fixed costs might be the rent paid for the firm’s building or equipment rentals. 2 Total Variable costs (TVC): These are costs that depend on the quantity output produced. - As the name suggests, these are costs associated with the variable inputs. - In the case of John’s Woodworking shop, the TVC = w × L where w denotes the wage rate. Total Costs = TFC + TVC. Herriges (ISU) Ch. 12 Behind the Supply Curve Fall 2010 13 / 30 Marginal Cost and Average Cost John’s Cost Structure Suppose that John has a TFC of $5000 and pays a wage rate of $1200 per week Units of Labor 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Herriges (ISU) Total Output 0 10 35 80 160 193 218 239 257 Total Fixed Cost (TFC) $5000 $5000 $5000 $5000 $5000 $5000 $5000 $5000 $5000 Total Variable Costs (TVC) $0 $1200 $2400 $3600 $4800 $6000 $7200 $8400 $9600 Ch. 12 Behind the Supply Curve Total Costs (TC) $5000 $6200 $7400 $8600 $9800 $11000 $12200 $13400 $14600 Fall 2010 14 / 30 Marginal Cost and Average Cost The Cost Curves Herriges (ISU) Ch. 12 Behind the Supply Curve Fall 2010 15 / 30 Marginal Cost and Average Cost Marginal and Average Cost Curves While the breakdown of Total Cost into Total Fixed and Total Variable Costs is helpful, two other measures of cost will be even more useful: 1 2 Marginal Cost: Measures the additional cost of producing one more unit of a good or service. Average Cost: Measures the average cost per unit of the good or service (i.e., the costs averaged over all of the output produced by the firm). Understanding the distinction between these two concepts will be key to finding the optimal level of production for the firm. We’ll start with average cost Herriges (ISU) Ch. 12 Behind the Supply Curve Fall 2010 16 / 30 Marginal Cost and Average Cost Average Costs There are three types of average costs 1 Average Fixed Costs (AFC) = Total Fixed Costs divided by Output TFC AFC = (1) Q Since the numerator is fixed, AFC will decline as output increases. 2 Average Variable Costs (AVC) = Total Variable Costs divided by Output TVC AVC = (2) Q - Since TVC is initial slowing down as output increases (with increasing returns to labor), AVC will initially fall as output increases. - As TVC starts to increase more rapidly with output (with diminishing returns to labor), AVC will start to increase with output. 3 Average Total Costs (ATC) = Total Costs divided by Output TC ATC = = AFC + AVC Q Herriges (ISU) Ch. 12 Behind the Supply Curve Fall 2010 (3) 17 / 30 Marginal Cost and Average Cost John’s Average Costs Units of Labor 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Herriges (ISU) Total Product 10 35 80 160 193 218 239 257 AFC $500.00 $142.86 $62.50 $31.25 $25.91 $22.94 $20.92 $19.46 Ch. 12 Behind the Supply Curve AVC $120.00 $68.57 $45.00 $30.00 $31.09 $33.03 $35.15 $37.35 ATC $620.00 $211.43 $107.50 $61.25 $56.99 $55.96 $56.07 $56.81 Fall 2010 18 / 30 Marginal Cost and Average Cost The Average Cost Curves Herriges (ISU) Ch. 12 Behind the Supply Curve Fall 2010 19 / 30 Marginal Cost and Average Cost Marginal Costs Another way of looking at the firm’s cost structure is to look at its Marginal Costs; i.e., how it’s costs increase as output increases. Formally: ∆TC MC = (4) ∆Q If we look at John’s Woodworking Shop we have Output 0 10 35 80 160 193 218 239 257 Herriges (ISU) Total Cost 5000 6200 7400 8600 9800 11000 12200 13400 14600 ∆Q ∆TC MC 10 25 45 80 33 25 21 18 1200 1200 1200 1200 1200 1200 1200 1200 120 48 27 15 36 48 57 67 Ch. 12 Behind the Supply Curve Fall 2010 20 / 30 Marginal Cost and Average Cost Adding in the MC Curve Herriges (ISU) Ch. 12 Behind the Supply Curve Fall 2010 21 / 30 Marginal Cost and Average Cost Patterns in the MC and AC Curves Notice that the MC curve is - Initially declining- this is due to increasing returns to labor - Eventually increasing- this is due to diminishing returns to labor The minimum-cost output, Q min , is the quantity at which the average total cost is lowest. - This is at the bottom of the ATC curve. - and occurs where ATC=MC At outputs less than Q min , ATC > MC and ATC is falling. At outputs greater than Q min , ATC < MC and ATC is rising. Herriges (ISU) Ch. 12 Behind the Supply Curve Fall 2010 22 / 30 Short-Run versus Long-Run Costs Production Costs in the Long Run Up until now, we have been focussing on the short-run, with some of the firm’s inputs held fixed. In the long run, costs behave differently Firm can adjust all of its inputs in any way it wants In the long run, there are no fixed inputs or fixed costs; i.e. all inputs and all costs are variable Firm must decide what combination of inputs to use in producing any level of output The firms goal is to earn the highest possible profit To do this, it must follow the least cost rule; i.e., to produce any given level of output the firm will choose the input mix with the lowest cost This yields a Long-Run Average Total Cost Curve; i.e., the relationship between the output and the ATC when fixed costs are chosen to minimize total cost for each level of output. Herriges (ISU) Ch. 12 Behind the Supply Curve Fall 2010 23 / 30 Short-Run versus Long-Run Costs Consider John’s Woodworking Shop Suppose that in our first production function, we assumed that John had only one set of tools (e.g., 1 table saw, 1 drill press, and 1 router table). We’ll call this one unit of capital The tools (and the space to house his tools) constitute fixed costs for John in the short-run. In the long-run, John must decide whether or not he wants to expand his capital stock The trade-off is that additional capital will avoid worker congestion, but imposes a large fixed cost on the firm. At low levels of production, having just one set of tools is not a binding constraint and John would rather avoid the additional capital costs. At higher levels of production, additional capital will avoid congestion problems and the capital costs are spread out over more units of production. Herriges (ISU) Ch. 12 Behind the Supply Curve Fall 2010 24 / 30 Short-Run versus Long-Run Costs Different Levels of Capital Labor Units of Labor 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Herriges (ISU) Units of Capital Capital = 1 Capital = 2 Capital = 3 0 0 0 10 10 10 35 39 39 80 92 101 160 184 202 193 284 314 218 397 439 239 443 571 257 478 709 Ch. 12 Behind the Supply Curve Fall 2010 25 / 30 Fall 2010 26 / 30 Short-Run versus Long-Run Costs The Corresponding ATC Figures are Given by Herriges (ISU) Ch. 12 Behind the Supply Curve Short-Run versus Long-Run Costs John’s Capital Stock Choice The level of capital stock John chooses depends on his expected level of output Herriges (ISU) Ch. 12 Behind the Supply Curve Fall 2010 27 / 30 Short-Run versus Long-Run Costs If Capital Stock Can be Varied Continuously, We Get Herriges (ISU) Ch. 12 Behind the Supply Curve Fall 2010 28 / 30 Short-Run versus Long-Run Costs Returns to Scale LRATC curves for industries usually exhibit three basic phases: 1 Increasing Returns to Scale: Output range with declining LRATC This is also known as economies of scale Economies of scale often arise due to the gains from specialization. The greatest opportunities for increased specialization occur when a firm is producing at a relatively low level of output Economies of scale can also arise due to minimum size requirements for certain types of equipment. 2 Constant Returns to Scale: Output range with constant LRATC Over some range of production, size may not matter and firms of the same size will be equally cost-effective. 3 Decreasing Returns to Scale: Output range with increasing LRATC This is also known as diseconomies of scale As output continues to increase, most firms will reach a point where bigness begins to cause problems This is true even in the long run, when the firm is free to increase its plant size as well as its workforce Diseconomies of scale are more likely at higher output levels Herriges (ISU) Ch. 12 Behind the Supply Curve Fall 2010 29 / 30 Fall 2010 30 / 30 Short-Run versus Long-Run Costs Herriges (ISU) Ch. 12 Behind the Supply Curve