A Portrait of Part-Time Faculty Members

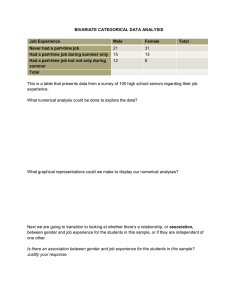

advertisement