A New Method for Estimating Nonsynonymous Substitutions and

Its Applications to Detecting Positive Selection

Hua Tang and Chung-I Wu

Department of Ecology and Evolution, University of Chicago

The standard methods for computing the number of nonsynonymous substitutions (Ka) lump all amino acid changes

into one single class, even though their rates of substitution vary by at least 10-fold (Tang et al., 2004). Classifying

these changes by their physicochemical properties has not been suitably effective in isolating the fastest evolving classes

of changes. We now propose to use the Universal index U of Tang et al. (2004) to classify the 75 elementary amino

acid changes (codons differing by 1 bp) by their evolutionary exchangeability. Let Ki denote the Ka value of each class

(i 5 1, ., 75 from the most to the least exchangeable). The cumulative Ki for the top 10 classes, denoted Kh (for highexchangeability types), has two important properties: (1) Kh usually accounts for 25%–30% of total amino acid changes and

(2) when the observed number of amino acid substitutions is large, Kh is predictably twice the value of Ka. This shall be

referred to as the twofold approximation. The new method for estimating Kh is applied to the comparisons between human

and macaque and between mouse and rat. The twofold approximation holds well in these data sets, and the signature of

positive selection can be more easily discerned using the Kh statistic than using Ka. Many genes with Ka/Ks . 0.5 can now be

shown to have Kh/Ks . 1 and to have evolved adaptively, at least for the high-exchangeability group of amino acid changes.

Introduction

The estimation of nucleotide changes is fundamental to

molecular evolutionary studies (Li, 1997). For coding

regions, a simple approach is to estimate the Ka (number

of nonsynonymous changes per nonsynonymous site) and

Ks (number of synonymous changes per synonymous site)

values separately (Li, Wu, and Luo, 1985; Nei and Gojobori,

1986; Yang and Bielawski, 2000). While synonymous

changes are weakly, and presumably more or less uniformly,

constrained, the strength of selective constraint varies

greatly among different types of amino acid mutations.

For example, both Ser to Thr and Cys to Tyr are nonsynonymous changes, but their rates of substitutions probably differ by more than 10-fold (Tang et al., 2004). Grouping

nonsynonymous changes that have similar evolutionary dynamics into separate categories is, therefore, likely to be

a useful strategy in discerning hidden patterns of molecular

evolution.

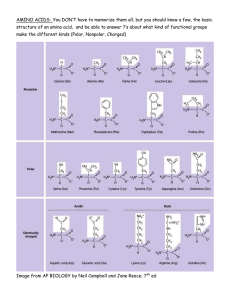

There are many ways to decompose nonsynonymous

changes into individual classes. For example, there have

been attempts at classifying the 20 amino acids into groups

according to their charge, polarity, volume, and so on.

Amino acid substitutions within groups are considered conservative, whereas those between groups are radical

(Zhang, 2000). Several other measures such as Grantham’s

distance have also been proposed to quantify the differences

between amino acids (Grantham, 1974). However, it does

not appear that amino acid changes so classified would have

comparable evolutionary dynamics (Rand, Weinreich, and

Cezairliyan, 2000; Zhang, 2000). Many amino acid

changes classified as conservative in fact evolved slowly,

whereas others so classified evolved much more rapidly

(Yang, Nielsen, and Hasegawa, 1998; Rand, Weinreich,

and Cezairliyan, 2000). The lack of consistency arose from

the nonempirical nature of amino acid classifications.

Key words: amino acid substitution, evolutionary index, positive

selection.

E-mail: ciwu@uchicago.edu.

Mol. Biol. Evol. 23(2):372–379. 2006

doi:10.1093/molbev/msj043

Advance Access publication October 19, 2005

Ó The Author 2005. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of

the Society for Molecular Biology and Evolution. All rights reserved.

For permissions, please e-mail: journals.permissions@oxfordjournals.org

An empirical system of classifying amino acid

changes by their evolutionary exchangeability has recently

been developed by Tang et al. (2004). Among the 20 amino

acids, there are 190 possible changes, of which only 75

kinds can be substituted with a 1-bp change in the codons.

Each of these 75 kinds of amino acid mutations is referred

to as an elementary amino acid change. The remaining 115

kinds are composites of two or three elementary changes. In

Tang et al. (2004), we estimated the evolutionary index

(EI(i), i 5 1–75) for each of the 75 kinds of changes. EI

is the equivalent of the Ka/Ks ratio for each kind. Between

closely related species, EIs can be accurately computed

when a large number of DNA sequences are available.

This method of EI for amino acid changes differs from

earlier systems in three important ways. First, EI is codon

based, whereas earlier methods such as the PAM matrix

(Dayhoff, Schwartz, and Orcutt, 1978) were based on amino

acid sequences. Second, EI is computed between closely related species, hence requiring a large number of DNA

sequences. Third, EIs among different gene sets from diverse taxa have been shown to be highly correlated. This

has led to the proposal of a universal measure of amino acid

exchangeability, U. For any large data set, we only need to

a/ K

s in order to compute the expected EIs,

know the mean K

which are linearly correlated with the constant scale, U.

One of the many reasons for separating synonymous

and nonsynonymous changes (and for classifying amino

acid substitutions) is to detect positive selection. If the

Ka/Ks ratio is significantly greater than 1, the sequence evolution is usually interpreted to be driven by positive selection, on the assumption that synonymous changes are the

proxy of neutral changes (Li, 1997). Although synonymous

changes are generally not neutral (Akashi, 1995; Hellmann

et al., 2003; Lu and Wu, 2005; discussed later), the Ka/Ks

ratio remains relatively free of assumptions for inferring the

action of natural selection.

The Ka/Ks . 1 test is perhaps overly stringent as it requires the acceleration in amino acid substitutions, due to

positive selection at some sites, to overcompensate for

the retardation at other sites due to negative selection. In this

study, we demonstrate how grouping amino acid changes by

The 2,369 pairs of orthologs between human and the

macaque monkey were aligned using the DNASTAR Megalign program. The 1,306 orthologs between mouse and rat

were taken from those used in Tang et al. (2004). To calculate the number of substitutions for each of the 75 classes

of elementary changes (Ki), large number of changes have

to be scored. In those cases, we use the mean weighted by

the gene length. It is equivalent to stringing together all

coding sequences to create a ‘‘supersequence.’’

pffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

Evaluation of ðKi* Ka Þ= VarðKi* Þ in U Data Sets

In any U data set, Ki is assumed to equal exactly

cUi ; i51; 2; .; 75; where c is a scaling factor equal to the av*

erage Ka of the

Pdata set. The

Pcumulative

PKi for the first

P i classes is Ki* 5 ij51 Kj Lj = ij51 Lj 5 ij51 cUj Lj = ij51 Lj ,

where Lj is the estimated length for jth-type amino acid

changes in the data set. VarðKi Þ can be approximated as

VarðKi Þ 5 pi ð1 pi Þ=½Li ð1 4pi =3Þ2 ; where pi 5 4=3

ð1 e4=3Ki Þ (Li, 1997). Between closely related species,

Ki 1 for i 5 1, 2, ., 75. Thus, VarðKi Þ can be further approximated as P

VarðKi Þ5KP

i =Li whichPthen gives

*

Þ 5 Varð ij51 Kj Lj ij51 Lj Þ5 ij51 cUj Lj =

rise

i

Pi to VarðK

ð j51 Lj Þ2 :

An optimal i (number of classes)pcan

be found

by

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

ffi

maximizing the quantity ðKi* Ka Þ= VarðKi* Þ (where

*

Þ

Ka [ K75

Ki* Ka

qffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

*

VarðKi Þ

.P

.P

Pi

P75

i

75

j 5 1 cUj Lj

j 5 1 Lj j 5 1 cUj Lj

j 5 1 Lj

rffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

5

.

Pi

Pi

2

j 5 1 cUj Lj ð

j 5 1 Lj Þ

.P

P75

Pi

pffiffiffiPi

75

c

j 5 1 Uj Lj j 5 1 Uj Lj 3

j 5 1 Lj

j 5 1 Lj

qffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

5

:

Pi

j 5 1 Uj Lj

pffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

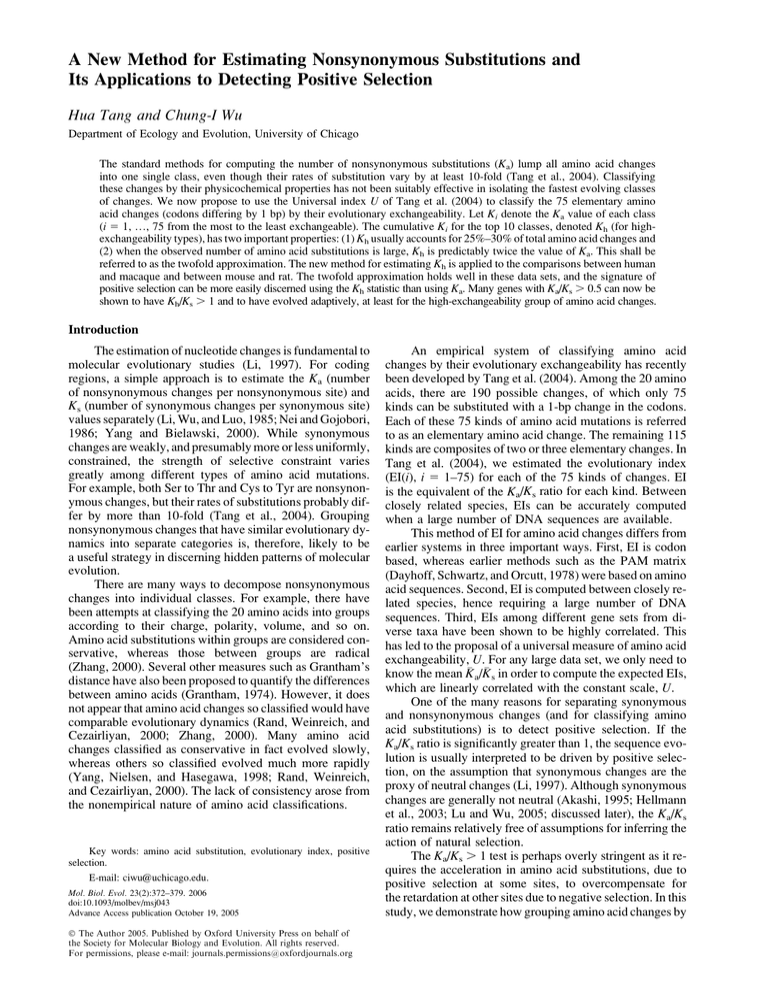

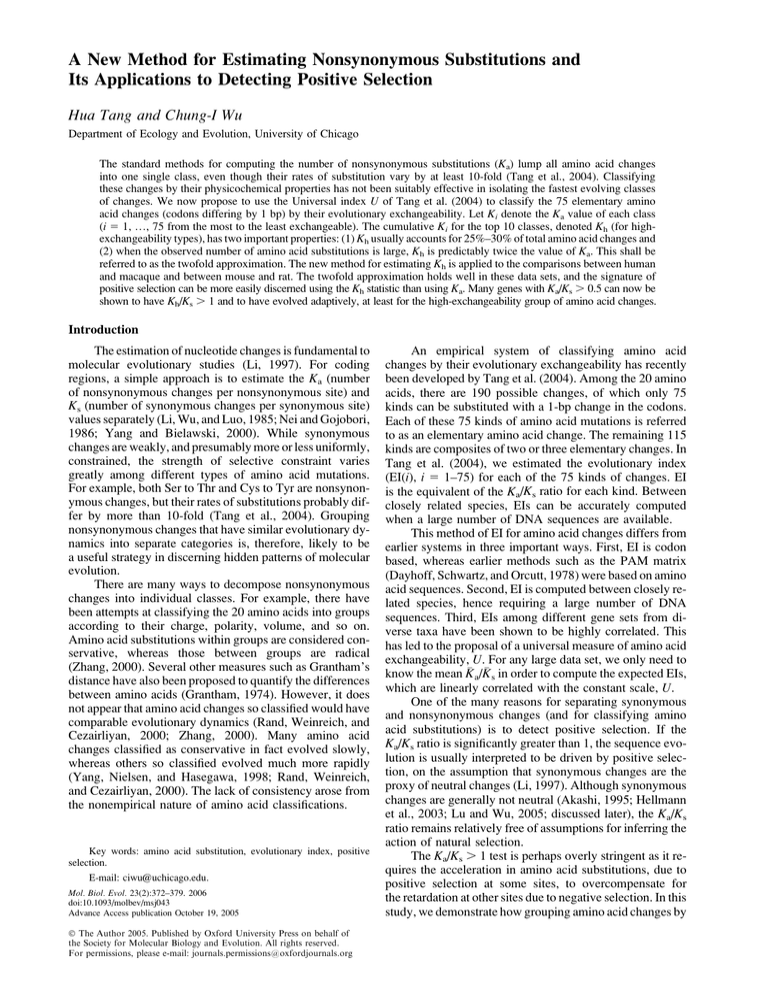

The optimal i at which ðKi* Ka Þ= VarðKi* Þ is

maximized does not depend on thep

exact

values

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

ffi of Li and

c. In figure 1, we plot ðKi* Ka Þ= VarðKi* Þ versus i by

choosing c 5 P

0.05 (equivalently, the average Ka is equal

75

to 0.05) and

i51 Li 510; 000 for convenience because

the general shapes are not affected by their values. Also

8

4

2

0.5

(K*i −Ka)/SD(K*i )

K*i /Ks

1.0

6

(K*i −Ka)/SD(K*i )

0

Materials and Methods

DNA Sequences

K*i /Ks

0.0

their U-index and computing the associated Ka/Ks values can

substantially augment the power of detecting the signature

of positive selection. Moreover, we establish the statistical

criteria for isolating the high-exchangeability amino acid

pairs from the rest. The average Ka value of this group will

be referred to as Kh, which generally accounts for 25%–30%

of total amino acid changes. We show that Kh on average is

about twice the value of Ka at the genomic level. There are

many cases where Kh/Ks . 1, indicating positive selection,

whereas the traditional Ka/Ks does not reveal adaptive

evolution.

1.5

Estimating Nonsynonymous Substitutions and Its Applications to Detecting Positive Selection 373

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

i

FIG. 1.—Ki* =Ks (thick solid line) and ðKi* KaÞ =SDðKi* Þ (open

circles) from a generalized U data set with a weighted average of Ka 5

0.05 and Ks 5 0.1 are evaluated. i denotes each class of elementary amino

acid change, ranging from 1 (most exchangeable) to 75 (least exchangeable). The more exchangeable classes with i 10 are separately analyzed.

*

=Ks (5Kh =Ks ) is slightly greater than 1 or twice the value of

Note that K10

the average Ka =Ks .

P

P

Ki* =Ks 5 ij51 cUj Lj = ij51 Lj ð1=Ks Þ versus i is plotted in

the same figure by choosing c/Ks 5 0.5 (i.e., the average

Ka/Ks of the data set is set to be 0.5). In our calculations,

we used the genome-wide frequencies of sites for the 75

kinds of elementary nonsynonymous changes for rodents

which are included in the Table S1 in the Supplementary

Material online. Because mammalian genome codon frequencies are highly correlated and genome-wide ts/tv biases

are similar, the exact genomes used for this purpose do not

matter much.

Results

Computing Nonsynonymous Substitutions of

the ith Kind, Ki (and Ki* )

The Ka value of a gene represents the average rate of

amino acid substitution for that gene. Nonsynonymous substitutions between some types of amino acid changes may

take place much faster than the average rate. Our objective

is to isolate the highly exchangeable types of amino acid

changes from the rest, based on our previous analysis of

two species of yeast and two species of rodents (Tang

et al., 2004). By the criteria of Tang et al. (2004), we classify the 75 kinds of elementary amino acid changes (those

that differ by 1 bp) by a universal ranking, Ui (see Table S1,

Supplementary Material online). In the Ui classification, i 5

1 denotes the most exchangeable (Ser 4 Thr in this case)

and i 5 75 the least exchangeable (Asp 4 Tyr) kind. Generally, the high-exchangeability pairs are more conservative

in their physicochemical properties. For comparison, we

also ranked the changes by (1) the increasing order of Grantham’s distance and (2) rankings by random permutations.

We show below how the Ka value for the ith class of

amino acid changes, referred to as Ki, is calculated. Ki/Ks is

the EI of the ith class, EI(i), as defined by Tang et al. (2004).

374 Tang and Wu

We also define Ki* as the cumulative Ki value of the first i

classes. Ki* is thus the weighted average of Kj for j from 1 to

*

is equivalent to Ka in the conventional cali. Note that K75

culation. The estimation we will introduce here is a simple

counting method, as a first attempt. More elaborate statistical methods will have to be developed and evaluated at

a later time.

Counting the Differences in the Synonymous Class and

Each of the 75 Elementary Amino Acid Change Classes

We first obtain the observed differences for the ithtype elementary amino acid change, Ni (i51, 2, ., 75),

as well as the total number of synonymous differences

Ns. For those codons differing by 2 bp, there are two pathways; for example, TTT–TTC–TCC or TTT–TCT–TCC.

We use the genome-wide EI (Tang et al., 2004) to assign

the probability for each of the two possible pathways. We

disregard the codons differing by 3 bp because they are very

rare between closely related species.

Counting the Synonymous and Nonsynonymous Sites

For genes with length L, we count the total number of

synonymous sites, Ls, and sites for each type of elementary

amino acid changes, Li (i 5 1, 2, ., 75). We assume mutations happen randomly on the sequences and obtain the

frequency of changes from amino acid j to amino acid k

( j 5 j or j 6¼ k);Pmutations to the stop codons are excluded.

Given L5Ls 1 75

i51 Li ; we can then calculate Ls and Li. The

counting method is similar to that in (Wyckoff, Wang,

and Wu, 2000) or Zhang (2000), except that we count

the number of sites for each of the 75 elementary changes

separately.

In enumerating the changes, the mutation pattern is

important. We consider only the difference between transition (ts) and transversion (tv). Dagan, Talmor, and Graur

(2002) showed that the ts/tv ratio has a profound effect

on the estimates of radical versus conservative amino acid

substitutions. Fortunately, Rosenberg, Subramanian, and

Kumar (2003) recently showed the ts/tv ratio to be relatively constant in each genome. Therefore, the genomewide ts/tv ratios (2.4 for primates and 1.7 for rodents)

estimated from the fourfold-degenerate sites were used in

the estimation.

Estimation of Ks, Ki, and Ki*

Given the observed changes (Ns and Ni, i 5 1, 75) and

the estimated number of sites (Ls and Li), we can estimate Ks

and Ki as Ns/Ls and Ni/Li, respectively. To account for multiple hits, we use the method of Jukes and Cantor (1969).

Note that the method developed in this paper is intended for

closely related species with less than 20% sequence divergence; thus, the following formulas were used:

4N s

Ks 5 0:75 ln 1 3 Ls

and

4Ni

:

Ki 5 0:75 ln 1 3 Li

Ki* ; the cumulative rate for the first i kinds of amino acid

changes, is

"

#

Pi

4 j 5 1 Nj

*

;

Ki 5 0:75 ln 1 Pi

3 j 5 1 Lj

where i 5 1, 2, ., 75.

Variance of Ks, Ki, and Ki*

Between species with a sequence divergence of 20%

or less, we suggest using the variance formulas of the

method of Jukes and Cantor (1969).

VarðKs Þ 5

ps ð1 ps Þ

2 ;

Ls 1 4p3s

pi ð1 pi Þ

VarðKi Þ 5 2 ;

Li 1 4p3 i

Pi ð1 Pi Þ

*

i;

VarðKi Þ 5 h

2 Pi

1 4P3 i

j 5 1 Lj

P

P

where ps 5Ns =Ls ; pi 5Ni =Li and Pi 5 ij51 Nj = ij51 Lj :

For larger data sets, we recommend bootstrapping as

an empirical means for estimating the variance of Ki, using

codons as the resampling units.

Application of the Ki Method to the Generalized

U Data Sets

One may have expected Ki to vary from one data set to

another (say, yeast vs. mammals), and the application of

this estimation method to different data sets would yield

different patterns. Fortunately, there is a strong correlation

among Ki’s. The salient finding of Tang et al. (2004) is that

EI(i)’s (5Ki/Ks) for different sets of genes from different

taxa are highly correlated. Hence, a Universal index, U,

was proposed (Table S1, Supplementary Material online)

such that EIs from any data set would be highly correlated

with U. For any data set with more than 20,000 amino acid

a =K

s Þ;

changes, EI(i) can be approximated by Ui 3 ðK

where Ka and Ks are, respectively, the (weighted) mean

nonsynonymous and mean synonymous substitution rates

of the entire data set. Ui’s are given in Table S1 (Supplementary Material online). For such data sets, the correlation

coefficient (r) between the observed EI(i) and the expected

a =K

s Þ is usually greater than 0.95. However, even

U i 3 ðK

smaller data sets with only 2,500 amino acid changes would

still yield an r value of .0.85 (Tang et al., 2004).

We shall refer to a collection of generalized data sets

as U sets, for which

a =K

s Þ for i 5 1 to 75: ð1Þ

EIðiÞ 5 Ki =Ks 5 Ui 3 ðK

a/K

s may differ from one data set to another. In any U set

K

(Tang et al., 2004), K1 =Ks is about 2.5 times, and K5 =Ks is

s. In figure 1, we

a/K

slightly more than twice, as high as K

show the decrease in Ki* as i increases; for example, K5* =Ks

a/ K

s(50.5 in

(.1.1) is more than 2.2 times the value of K

fig. 1). The result suggests, not surprisingly, that the highexchangeability classes of amino acid changes should be

more revealing of positive selection than the entire set of

Estimation of High-Exchangeability Substitutions,

*

Kh (5K10

), in Primates and Rodents

We shall now apply the Ki (or Kh) method to the genomic sequences of primates (human vs. macaque monkey)

and rodents (mouse vs. rat).

The Distribution of Ka/Ks in Primates and Rodents

In figures 2a and 2b, we show the distributions of the

Ka/Ks ratios for primates and rodents. The weighted means

are 0.176 and 0.148 for the primate and rodent comparisons, respectively. Only 21 out of 2,369 genes in the primate data show a Ka/Ks ratio greater than 1 (including 7

genes with Ks 5 0). In rodents, 7 out of 1,306 genes have

Ka/Ks . 1. In none of these comparisons is Ka . Ks significant. In other words, the conventional Ka/Ks analysis reveals little signature of positive selection in these data sets.

Ka versus Kh Among the Fastest Evolving Genes in

Primates and Rodents

In either data set, we first analyzed the top 100 genes

with the highest Ka values as shown in figure 3. The fastest

evolving 100 genes in primates and rodents have a mean Ka/

Ks ratio of 0.72 and 0.60, respectively. In figure 3, the cumulative Ki* =Ks values for the concatenated sequences are

plotted against i (thick black line). The curve in figure 3

decreases monotonically as i increases.

Among the conservative changes in primates (i , 20)

(fig. 3a), the cumulative Ki* =Ks ratios are greater than 1,

300

200

150

number of genes

100

0

0

50

200

number of genes

250

600

Defining Nonsynonymous Substitutions for the

High-Exchangeability Class (Kh)

For small i’s, Ki* (such as K5* ) in a generalized data set

is much higher than the standard Ka but the standard deviation (SD) associated with the estimate of K5* is also relatively large. If we include more classes of amino acid

changes (say, i . 30), the estimation error would be smaller

but Ki* =Ks would also decrease. There is a trade-off in the

demarcation of high- and low-exchangeability classes. An

optimal number of classes in this trade-off is about 10–12,

as shown below.

In figure 1, we plot ðKi* Ka Þ=SDðKi* Þ against i where

SDðKi* Þ is the SD of Ki* Note that ðKi* Ka Þ=SDðKi* Þ increases and reaches a plateau between i 5 10 and i 5 25.

(The general shape and position of the plateau in figure 1 are

not affected much by the total length of genes because we

are comparing the relative values among different Ki* ’s.)

One may wish to maximize both ðKi* Ka Þ=SDðKi* Þ and

ðKi* Ka Þ: To do so, we recommend the i value to be between 10 and 12, corresponding to where the curve in figure

1 reaches the plateau.

In general, the top 10–12 classes account for 25%–

30% of the total number of amino acid differences ob*

*

=Ks or K12

=Ks is slightly above or below twice

served. K10

the conventional Ka =Ks : We shall refer to this pattern as the

‘‘twofold approximation,’’ which will be tested further by

*

will be designated Kh (h

using published genomic data. K10

for high exchangeability) from now on.

(b)

(a)

400

changes. The question ‘‘what demarcates high- and lowexchangeability classes?’’ is addressed in the next section.

350

Estimating Nonsynonymous Substitutions and Its Applications to Detecting Positive Selection 375

0.0

0.4

Ka/Ks

0.8 >1

0.0

0.4

0.8 >1

Ka/Ks

FIG. 2.—(a) The distribution of Ka/Ks for 2,369 orthologous genes

between human and the macaque monkey. (b) The distribution of Ka/Ks

for 1,306 genes between mouse and rat.

hinting the action of positive selection. (Note that the ranking by i was independent of the data of figure 3a; it was

determined in Tang et al. [2004] using different data sets.)

As i approaches 75, the cumulative Ki* =Ks value approaches

0.72, which is the mean Ka/Ks. The inclusion of more radical classes of amino acid changes, on which negative selection operates strongly, masks the signature of positive

*

as noted; Kh/Ks is

selection. We use Kh to designate K10

1.494, about twice the Ka/Ks ratio of 0.72.

To show the significance of the difference between Kh/

Ks and Ka/Ks, we randomly shuffled the i ranking and determined that the differences observed after the ranking is shuffled 1,000 times. For each i value, the highest 5% in Ki* =Ks as

well as the means are plotted in figure 3a. The dashed line also

decreases monotonically because the SD of Ki* decreases

when i becomes larger with more samples. At each i, the observed Ki* =Ks is always bigger than the highest 5% value in

the randomized ranking scenarios. The observed excess is

thus statistically significant for every i rank.

We also tested other ranking methods in the literature.

The long-dashed line presents Ki* =Ks calculations based on

the ranking by Grantham’s distance (Grantham, 1974). The

line moves up and down but never goes above 1. This irregular pattern confirms what has been reported—that

amino acid changes determined to be conservative by Grantham’s distance are often pairs of low exchangeability

(Yang, Nielsen, and Hasegawa, 1998). Grantham’s distance

thus does not provide a suitable ranking of the substitution

rate between amino acids. We obtained the same pattern for

the top 100 genes in rodents (fig. 3b).

Ka versus Kh Among All Genes in Primates and Rodents

Although the Ki method is most useful when large

number of substitutions can be analyzed, Kh can be applied

2.0

376 Tang and Wu

K*i /Ks

1.5

amino acid ranking based on U index(conservtive−−>radical)

amino acid ranking based on Grantham Distance(increasing order)

top 5% from simulation based on the random ranking

mean from simulation based on the random ranking

0.5

1.0

(a): primate sequences

0

10

30

20

40

50

70

60

1.4

i

1.0

(b): rodent sequences

0.6

0.8

K*i /Ks

1.2

amino acid ranking based on U index(conservtive−−>radical)

amino acid ranking based on Grantham Distance(increasing order)

top 5% from simulation based on the random ranking

mean from simulation based on the random ranking

0

10

20

30

40

50

70

60

i

FIG. 3.—(a) The Ki* =Ks values for the concatenated 100 fastest evolving genes from primates are plotted against i (1–75) using three different

rankings: (1) the decreasing order by the U-index (thick black line); (2) the increasing order of Grantham’s distance (long-dashed line); (3) random

order (the highest 5% and the mean are plotted as dashed and dotted lines, respectively). (b) Same as (a) but using rodent sequences.

to individual genes as well. For each individual gene, we

calculated the Kh, Ka, and Ks values. In Table 1, we present

20 such examples, 10 from each data set. These are examples of longer genes and hence smaller stochastic fluctuations. In general, Kh is indeed larger than Ka for longer

genes, but the variance for each individual gene is substan-

tial. The new method is more informative when many genes

are analyzed simultaneously, as shown below.

The scatter plot of Kh/Ks versus Ka/Ks for the 1,948

genes between human and macaque (excluding those with

Ka 5 0 or Ks 5 0) is shown in figure 4a. Among those

genes, only 14 have a Ka/Ks ratio greater than 1. In contrast,

Table 1

Examples for the Estimation of Ks, Ka, and Kh

Data Set

Accession

Gene Name

Number of Codons

Ks

SE(Ks)

Ka

SE(Ka)

Kh

SE(Kh)

Ka/Ks

Kh/Ks

Primate

NM_133259

AF103801

NM_000313

NM_001063

NM_002087

NM_017646

NM_006059

BC010570

NM_015392

NM_002615

NM_013016

NM_012705

NM_032082

NM_130409

NM_057193

NM_012830

NM_017300

NM_053781

NM_012503

NM_130424

LRPPRC

Unknown

PROS1

TF

GRN

IPT

LAMC3

HMGCL

NPDC1

SERPINF1

Ptpns1

Cd4

Hao2

Cfh

Il10ra

Cd2

Baat

Akr1b7

Asgr1

Tmprss2

714

486

327

690

588

326

501

325

320

416

508

455

353

1,233

569

342

419

316

284

490

0.0616

0.0672

0.0389

0.0743

0.0635

0.0504

0.0779

0.0817

0.1021

0.1264

0.1055

0.1630

0.1297

0.1619

0.1698

0.1960

0.1638

0.1693

0.1765

0.1722

0.0101

0.0126

0.0118

0.0114

0.0114

0.0136

0.0132

0.0173

0.0190

0.0193

0.0162

0.0220

0.0220

0.0137

0.0201

0.0285

0.0231

0.0274

0.0295

0.0223

0.0575

0.0493

0.0265

0.0427

0.0339

0.0220

0.0334

0.0209

0.0236

0.0237

0.1152

0.1452

0.0925

0.1062

0.0991

0.1104

0.0782

0.0746

0.0556

0.0501

0.0064

0.0072

0.0063

0.0055

0.0053

0.0057

0.0058

0.0056

0.0061

0.0053

0.0110

0.0132

0.0116

0.0067

0.0095

0.0130

0.0097

0.0109

0.0098

0.0071

0.1146

0.1540

0.0834

0.1142

0.0665

0.0481

0.0543

0.0187

0.0846

0.0379

0.2188

0.1958

0.1971

0.2204

0.1139

0.2308

0.1962

0.1636

0.0541

0.1147

0.0251

0.0402

0.0299

0.0284

0.0264

0.0242

0.0235

0.0150

0.0430

0.0191

0.0423

0.0432

0.0480

0.0285

0.0280

0.0572

0.0451

0.0466

0.0278

0.0308

0.9325

0.7336

0.6829

0.5747

0.5331

0.4375

0.4290

0.2562

0.2313

0.1877

1.0925

0.8907

0.7133

0.6561

0.5834

0.5633

0.4773

0.4407

0.3152

0.2911

1.8584

2.2923

2.1471

1.5367

1.0463

0.9539

0.6973

0.2293

0.8294

0.2999

2.0750

1.2009

1.5191

1.3617

0.6706

1.1771

1.1976

0.9659

0.3062

0.6659

Rodent

These genes were chosen from the primate and rodent data sets mainly on account of their lengths. Examples are given in the descending order of Ka/Ks in each data set.

1.4

1.2

4

1.2

y =2.005x + 0.0122

y=1.9428x + 0.02724

R2= 0.9856

R2= 0.9926

0.8

1.2

Ka/Ks

FIG. 4.—The scatter plots of Kh/Ks versus Ka/Ks for (a) 1,948 orthologs between human and macaque and (b) 1,241 orthologs between mouse

and rat. The dashed lines are fitted regression lines. Those points with Kh/

Ks . 4.0 are plotted on the upper edge. Note that the slopes of the regression lines in both panels are greater than 2.

Kh/Ks is larger than 1 in 174 genes. Most data points in

figure 4a are well above the 45° line; data points below the

45° line are generally genes with small Ka. We also analyzed 1,241 orthologs between rat and mouse, as shown

in figure 4b. In this comparison, 7 genes show Ka/Ks greater

than 1 but for Kh/Ks 92 genes do. In both panels, the slopes

of the regression lines are above 2, indicating that Kh/Ks

is at least twice the value of Ka/Ks on average.

It should be noted that Kh/Ks may often be larger than 1

due to the larger standard error (SE) of Kh, in addition to its

larger mean. To remove, or at least reduce, the contribution

of the larger SE, we examine the correlation between Kh SE(Kh) and Ka SE(Ka). Both data sets show that they are

highly positively correlated with the correlation coefficient

larger than 0.75, and on average the Kh SE(Kh) is approximately 1.7 times the value of Ka SE(Ka). Moreover, for

those genes with Kh/Ks . 1, Kh 2SE(Kh) is on average

1.29 times higher than Ka 2SE(Ka) for rodents and

1.13 times higher for primates. These results suggest that

the larger Kh/Ks ratios in most cases are indeed due to the

larger mean in Kh.

The ‘‘Twofold Approximation’’ of Kh versus Ka

In the generalized data sets, we show Kh ’ 2Ka. To test

the idea that genes of sufficient size will reliably yield the

twofold relationship, Kh ’ 2Ka, we concatenated genes

with similar Ka values. Of the 2,369 orthologs between human and macaque, we sorted the 1,955 genes with Ka .

0 by the descending order of Ka and concatenated every

50 orthologs into a supersequence. A total of 39 supersequences were obtained. In figure 5a, we plot Kh/Ks against

Ka/Ks for these supersequences. The correlation coefficient

r is 0.993, and the slope of the regression line is 2.005.

Therefore, the Kh/Ks ratio is very close to twice the value

of Ka/Ks, as shown in figure 1 for the generalized data set.

We applied the same procedure to 1,200 orthologs between

0.8

Kh/Ks

0.4

0.2

(a)

(b)

0.0

0.4

0.2

0.4

Ka/Ks

0.0

0.0

0.0 0.5 1.0 1.5 2.0

(b)

0

0

(a)

0.6

0.8

0.6

Kh/Ks

2

Kh/Ks

y = 2.47x − 0.067

2

R = 0.52

1

2

1

Kh/Ks

1.0

3

3

y = 2.06x − 0.016

R2 = 0.74

1.0

4

Estimating Nonsynonymous Substitutions and Its Applications to Detecting Positive Selection 377

0.0

0.2

0.4

Ka/Ks

0.6

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

Ka/Ks

FIG. 5.—(a) The scatter plot of Kh/Ks versus Ka/Ks for 39 supersequences between human and macaque. Each supersequence is the concatenation of 50 genes with similar Ka values. (b) The same plot for 24

supersequences between mouse and rat. Note that the slopes of both regression lines are around 2, indicating Kh/Ks is usually twice as large

as Ka/Ks.

mouse and rat, creating 24 supersequences (each again being a 50 gene contig). In figure 5b, the correlation coefficient between Kh/Ks and Ka/Ks is 0.996, and the slope is

1.943. Again, the twofold approximation holds quite well.

In summary, Kh’s in any sequence comparisons would

fluctuate, but generally hover about two times of the corresponding Ka value. For longer sequences (or collection

of sequences), the Kh ’ 2Ka approximation holds well.

Discussion

The study of coding sequence evolution generally

relies on the distinction between synonymous and nonsynonymous changes. The latter is a heterogeneous class

driven by forces that both accelerate and retard the rate

of molecular evolution. The signals of positive and negative

selection can be better resolved when nonsynonymous

changes are properly classified. The power of the method

lies in the empirical means of finding the right set of conservative amino acid changes. The relative ranking of most

to least exchangeable replacements applies equally well to

yeasts, Drosophila, plants, and mammals (Tang et al.,

2004). This consistency permits a universal delineation

of the optimal set of the top 10 classes of amino acid

changes. The ranking of amino acid properties is crucial

as other existing indices, such as the most widely used

Grantham’s distance, cannot delineate a subset of changes

that evolve substantially faster than the rest (fig. 3).

The method proposed here requires genomic sequences

from only two closely related species; hence, the influx of

genomic data should make the method widely applicable.

The downside of calculating Kh is the larger SE associated

with only a subset of changes. (Although it is defined by 10

of the 75 types of elementary changes, Kh usually accounts

378 Tang and Wu

for 25%–30% of the amino acid substitutions.) In this study,

a simple counting method is introduced. While it may be

sufficient to accurately estimate the divergence between

closely related species, the potential for more sophisticated

methods, such as maximum likelihood (ML) estimation under the Bayesian framework, should not be overlooked.

By examining the top 10 classes (or about 25%) of

amino acid changes, it becomes much easier to find cases

where nonsynonymous changes outpace synonymous ones

both at the genomic and genic levels. Because Ka . Ks is

taken to indicate the action of positive selection in most

methods (discussed below), Kh . Ks should be interpreted

in the same manner. Although Ks has been known to be

lower than the neutral substitution rate, by as much as

20% in some taxa (Akashi, 1995; Hellmann et al., 2003;

Lu and Wu, 2005), Ka (or Kh) . Ks remains a reasonable

criterion for inferring positive selection. Without invoking

positive selection on amino acid changes, the alternative interpretation would have to be that amino acid changes are

subjected to weaker selective constraints than synonymous

changes are. It seems more reasonable to assume that, on

average, selective constraints on nonsynonymous changes

are at least as strong as those on synonymous changes.

In figure 4 on mammalian genes, Kh fluctuates greatly

among individual genes, but the regression corroborates the

relationship of Kh ’ 2Ka. A source of the fluctuation is codon composition. Different codon compositions yield different estimations due to the weight for each type of change.

There are many other sources of variation, such as neighboring effect, gene structure, and selection constraints for

different types of amino acid changes in different genes.

Nevertheless, if each gene is sufficiently large, the codon

composition will be close to the genome average and the

relationship, Kh ’ 2Ka will be approached.

There are several other approaches to detecting positive selection. A most widely used method is the site-by-site

analysis of a set of DNA sequences (Nielsen and Yang,

1998; Suzuki and Gojobori, 1999). In this approach, the

proportion of sites in the sequences under positive selection

is estimated, often in the ML framework (Yang, 1998; Yang

and Nielsen, 2002). Although the method has been applied

to genomic sequences from as few as three species (Clark

et al., 2003), it is probably more suited to cases where

a much larger number of taxa can be used. Some recent

studies have also raised the issue of possible high rate of

false positives in the more elaborate ML models (Zhang,

2004). More recently, Massingham and Goldman (2005)

demonstrated an improved ML method, that is, sitewise

likelihood ratio (SLR), for detecting nonneutral evolution.

They showed that the SLR method can be more powerful,

especially in difficult cases where the strength of selection

is low. Most other approaches require additional functional

(Hughes and Nei, 1988; Wyckoff, Wang, and Wu, 2000),

chromosomal (Betancourt, Presgraves, and Swanson, 2002;

Lu and Wu, 2005), or polymorphism data (McDonald and

Kreitman, 1991; Fay, Wyckoff, and Wu, 2002) for inferring

positive selection. A recent method that needs less information than our proposed method is the so-called ‘‘volatility

measure’’ (Plotkin, Dushoff, and Fraser, 2004) which uses

only sequences from one single genome. The utility of this

method in detecting selection, however, remains to be

demonstrated (Chen, Emerson, and Martin, 2005; Dagan

and Graur, 2005; Hahn et al., 2005).

In conclusion, in addition to the conventional Ka and

Ks estimates, the calculation of Kh may often yield additional information. This is especially true when one attempts to compare two genomic sequences. Although the

statistical variation associated with Kh is larger than the conventional Ka, genes with high Kh/Ks ratios may reveal more

evolutionary signature and can then be subjected to additional analysis (McDonald and Kreitman, 1991; Yang,

1998; Fay and Wu, 2000) or experimentation (Greenberg

et al., 2003; Sun, Ting, and Wu, 2004).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table S1 is available at Molecular Biology and Evolution online (http://www.mbe.oxfordjournals.

org/).

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Hurng-Yi Wang for providing the alignments of primate orthologs used in this study.

The authors also thank Alex Kondrashov, Wen-Hsiung Li,

Martin Kreitman, and Jian Lu for comments and discussions. The work is supported by National Institutes of

Health grants to C.-I.W.

Literature Cited

Akashi, H. 1995. Inferring weak selection from patterns of polymorphism and divergence at ‘‘silent’’ sites in Drosophila DNA.

Genetics 139:1067–1076.

Betancourt, A. J., D. C. Presgraves, and W. J. Swanson. 2002. A

test for faster X evolution in Drosophila. Mol. Biol. Evol.

19:1816–1819.

Chen, Y., J. J. Emerson, and T. M. Martin. 2005. Evolutionary

genomics: codon volatility does not detect selection. Nature

433:E6–E7[discussion E7–E8].

Clark, A. G., S. Glanowski, R. Nielsen et al. (17 co-authors). 2003.

Inferring nonneutral evolution from human-chimp-mouse

orthologous gene trios. Science 302:1960–1963.

Dagan, T., and D. Graur. 2005. The comparative method rules! Codon volatility cannot detect positive Darwinian selection using

a single genome sequence. Mol. Biol. Evol. 22:496–500.

Dagan, T., Y. Talmor, and D. Graur. 2002. Ratios of radical to

conservative amino acid replacement are affected by mutational and compositional factors and may not be indicative

of positive Darwinian selection. Mol. Biol. Evol.

19:1022–1025.

Dayhoff, M. O., R. M. Schwartz, and B. C. Orcutt 1978. A model

of evolutionary change in proteins. National Biomedical Research Foundation, Washington.

Fay, J. C., and C. I. Wu. 2000. Hitchhiking under positive Darwinian selection. Genetics 155:1405–1413.

Fay, J. C., G. J. Wyckoff, and C. I. Wu. 2002. Testing the neutral

theory of molecular evolution with genomic data from Drosophila. Nature 415:1024–1026.

Grantham, R. 1974. Amino acid difference formula to help explain

protein evolution. Science 185:862–864.

Greenberg, A. J., J. R. Moran, J. A. Coyne, and C. I. Wu. 2003.

Ecological adaptation during incipient speciation revealed by

precise gene replacement. Science 302:1754–1757.

Hahn, M. W., J. G. Mezey, D. J. Begun, J. H. Gillespie, A. D.

Kern, C. H. Langley, and L. C. Moyle. 2005. Evolutionary

Estimating Nonsynonymous Substitutions and Its Applications to Detecting Positive Selection 379

genomics: codon bias and selection on single genomes. Nature

433:E5–E6[discussion E7–E8].

Hellmann, I., S. Zollner, W. Enard, I. Ebersberger, B. Nickel, and

S. Paabo. 2003. Selection on human genes as revealed by comparisons to chimpanzee cDNA. Genome Res. 13:831–837.

Hughes, A. L., and M. Nei 1988. Pattern of nucleotide substitution

at major histocompatibility complex class I loci reveals overdominant selection. Nature 335:167–170.

Jukes, T. H., C. R. Cantor. 1969. Evolution of protein molecules.

P. 21 in H. N. Munroe, ed. Mammalian protein metabolism.

Academic Press, New York.

Li, W.-H. 1997. Molecular evolution. Sinauer Associates, Inc.

Sunderland, Mass.

Li, W. H., C. I. Wu, and C. C. Luo. 1985. A new method for estimating synonymous and nonsynonymous rates of nucleotide

substitution considering the relative likelihood of nucleotide

and codon changes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2:150–174.

Lu, J., and C. I. Wu. 2005. Weak selection revealed by the wholegenome comparison of the X chromosome and autosomes of

human and chimpanzee. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA

102:4063–4067.

Massingham, T., and N. Goldman. 2005. Detecting amino acid

sites under positive selection and purifying selection. Genetics

169:1753–1762.

McDonald, J. H., and M. Kreitman. 1991. Adaptive protein

evolution at the Adh locus in Drosophila. Nature 351:

652–654.

Nei, M., and T. Gojobori. 1986. Simple methods for estimating

the numbers of synonymous and nonsynonymous nucleotide

substitutions. Mol. Biol. Evol. 3:418–426.

Nielsen, R., and Z. Yang. 1998. Likelihood models for detecting

positively selected amino acid sites and applications to the

HIV-1 envelope gene. Genetics 148:929–936.

Plotkin, J. B., J. Dushoff, and H. B. Fraser. 2004. Detecting selection using a single genome sequence of M. tuberculosis

and P. falciparum. Nature 428:942–945.

Rand, D. M., D. M. Weinreich, and B. O. Cezairliyan. 2000.

Neutrality tests of conservative-radical amino acid changes

in nuclear- and mitochondrially-encoded proteins. Gene

261:115–125.

Rosenberg, M. S., S. Subramanian, and S. Kumar. 2003. Patterns

of transitional mutation biases within and among mammalian

genomes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 20:988–993.

Sun, S., C. T. Ting, and C. I. Wu. 2004. The normal function

of a speciation gene, Odysseus, and its hybrid sterility effect.

Science 305:81–83.

Suzuki, Y., and T. Gojobori. 1999. A method for detecting positive selection at single amino acid sites. Mol. Biol. Evol.

16:1315–1328.

Tang, H., G. J. Wyckoff, J. Lu, and C. I. Wu. 2004. A universal

evolutionary index for amino acid changes. Mol. Biol. Evol.

21:1548–1556.

Wyckoff, G. J., W. Wang, and C. I. Wu. 2000. Rapid evolution of

male reproductive genes in the descent of man. Nature

403:304–309.

Yang, Z. 1998. Likelihood ratio tests for detecting positive selection and application to primate lysozyme evolution. Mol. Biol.

Evol. 15:568–573.

Yang, Z., and J. P. Bielawski. 2000. Statistical methods for detecting molecular adaptation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 15:496–503.

Yang, Z., and R. Nielsen. 2002. Codon-substitution models for

detecting molecular adaptation at individual sites along specific lineages. Mol. Biol. Evol. 19:908–917.

Yang, Z., R. Nielsen, and M. Hasegawa. 1998. Models of amino

acid substitution and applications to mitochondrial protein

evolution. Mol. Biol. Evol. 15:1600–1611.

Zhang, J. 2000. Rates of conservative and radical nonsynonymous

nucleotide substitutions in mammalian nuclear genes. J. Mol.

Evol. 50:56–68.

———. 2004. Frequent false detection of positive selection by the

likelihood method with branch-site models. Mol. Biol. Evol.

21:1332–1339.

Jianzhi Zhang, Associate Editor

Accepted October 10, 2005