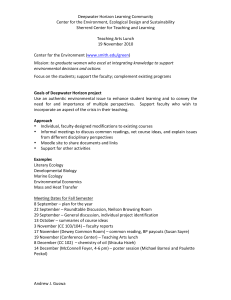

Checking Proof: Please Read Carefully

advertisement

A d v a n c i n g E n v i r o n m e n t a l Pr o t e c t i o n T h r o u g h • A n a l y s i s • O p i n i o n • D e b a t e Checking Proof: Please Read Carefully Attached are your galleys — a proof of the edited version of your article — for your approval. Please read carefully and make any necessary corrections in the large center margin provided for this purpose. Changes should be made clearly in pen in the center margin only, using standard proofreading marks. You should use an arrow or a carat, or black out text to be replaced, to indicate where the change is to go. Extensive changes or insertions may be made on a separate sheet (or sent via email to dujack@eli.org) and indicated by a notation such as “Insert A” at the appropriate point. Your galleys have a substantial amount of formatting. Please do not copy the text into a word processing document. In addition, please do not use the markup features of Adobe Acrobat — they are very difficult to handle. PLEASE, only make corrections in pen in the center margin of the galleys. When done, fax back the proof and this form to 434 296 1396. Emailing a scanned version is also acceptable. Thank you for your attention to these important procedures, which are vital for producing an error-free article. . Stephen R. Dujack, Editor 3730 West Dr., Charlottesville, VA 22901 Phone: 434 296 3380 Fax: 434 296 1396 Email: dujack@eli.org Please fax checking proof to 434 296 1396 Galley Proof — The Environmental Forum Regulating by Regulators, Not Industry Rebecca M. Bratspies C hants of “drill, baby, drill” had hardly faded from the public mind when BP’s Deepwater Horizon exploded, killing 11 workers and spewing massive amounts of oil into the Gulf of Mexico. The catastrophe highlights just how inadequate regulatory oversight over off-shore drilling had been. But, regulatory failures surrounding Deepwater Horizon extend well beyond a lone agency captured by the industry it was supposed to regulate. The BP disaster marks the failure of deregulation itself. For two decades, the American people have repeatedly been told that private actors could be trusted to protect public interests. Coupled with a naïve faith in technology, the assumption that market forces could replace government oversight drove calls for deregulation, voluntary compliance, and cooperative regulation — the hallmarks of recent United States regulatory policy. Steeped in a “we’re all on the same team” mentality, understaffed regulators allowed industry to write the rules and then assess their own compliance with those rules. The revolving door between government and the private sector created an overly cozy relationship in which private interests replaced public interests. BP and the rest of the oil industry took full advantage of this lax oversight to cut corners on environmental safety. How many times were we assured that off-shore oil production posed little risk? Or that the new technologies ensured oil extraction “would not have an effect, cumulatively or individually on the environment.” Industry consultants Galley Proof 1 ❧ mass-produced generic environmental assessments, and the Minerals Management Service blithely rubberstamped assertions that accidents would easily be handled. Now we see just how badly things can go wrong when regulators abdicate their watchdog function. Among the lessons to be learned from the Deepwater Horizon disaster are two key principles that apply across the modern regulatory state. First, we must take risks seriously. Until April 20, few people considered what would happen if an offshore rig exploded and then sank, causing oil to gush uncontrollably into the ocean. The Coast Guard did, but nobody listened to their 2002 call for rigorous regulatory oversight to ensure that safety and cleanup technology kept pace with extraction technology. Indeed one of the most striking aspects of this catastrophe was how industry and regulators alike completely disregarded the systemic risks inherent in deepwater drilling. Industry had no capacity whatsoever to respond to a deepwater blow-out. Instead, the oil industry assumed no such accident would occur. And regulators let them. As a result, three months into the spill, BP cannot stop the flow of oil — nor are it likely to do so anytime soon. Going forward, the risk of catastrophic failure must be planned for — with no exceptions. Generic regional plans are no substitute for real response plans for individual wells. Regulators should require sitespecific worst-case scenario planning before issuing any leases or permits. This approach requires industry to forecast what will happen if things go disastrously wrong for a specific well in a specific location. Armed with this information, industry would need to have technology in hand, before drilling commences, to reduce risks of that worst-case scenario as much as feasible, and to fix things, should an accident occur. For example, Canada requires that relief wells be drilled alongside any Please Edit in Pen or Pencil only and fax corrections to 434 296 1396 Galley Proof — The Environmental Forum permitted well — the United States should as well. Second, we must unprivatize regulation. Private actors should never be in the position of setting standards. Allowing them to do so guarantees that the resulting standards will not be technology-forcing, and increases the likelihood that inexpensive approaches will be favored, even when demonstrably less effective. Private actors have one overriding concern — their bottom line. All corporate decisions, by law, must be made for the benefit of shareholders. Too often, this translates into focusing on short-term, easily monetized benefits. Regulation, by contrast should protect the public’s long-term interests, and must care about unquantifiable benefits. Protecting endangered marine and shore animals, a thriving local economy, healthy wetlands — these are vital public interests that are simply not on the corporate radar screen. Private actors systematically discount risks to these public goods and overvalue benefits to themselves. Only regulators, acting in the public interest, can develop regulatory standards that will fully protect these public interests. As Deepwater Horizon demonstrates, we can and must do better. Instead of adopting “hoping for the best” as official policy, we need robust, independent, and adequately funded regulation focused on protecting the public’s right to a clean, safe, and healthy environment. Rebecca Bratspies teaches environmental law at CUNY School of Law. She is a member scholar of the Center for Progressive Reform. Galley Proof 2 ❧ Please Edit in Pen or Pencil only and fax corrections to 434 296 1396