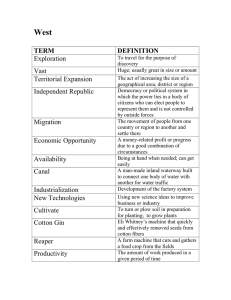

White Gold - The True Cost of Cotton

advertisement