Belief through Thick and Thin

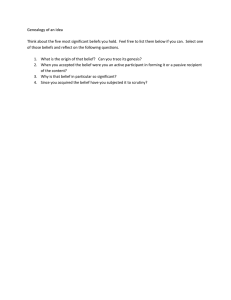

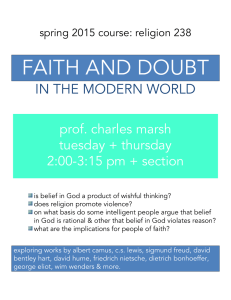

advertisement