The Promise of Business Doctoral Education

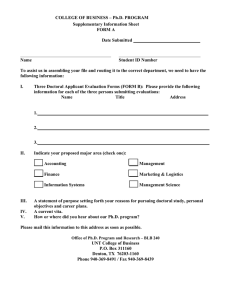

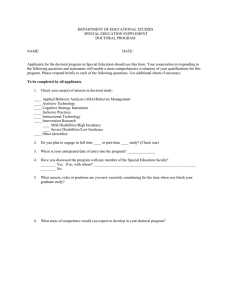

advertisement