Introduction to Seven Elements of Interest

advertisement

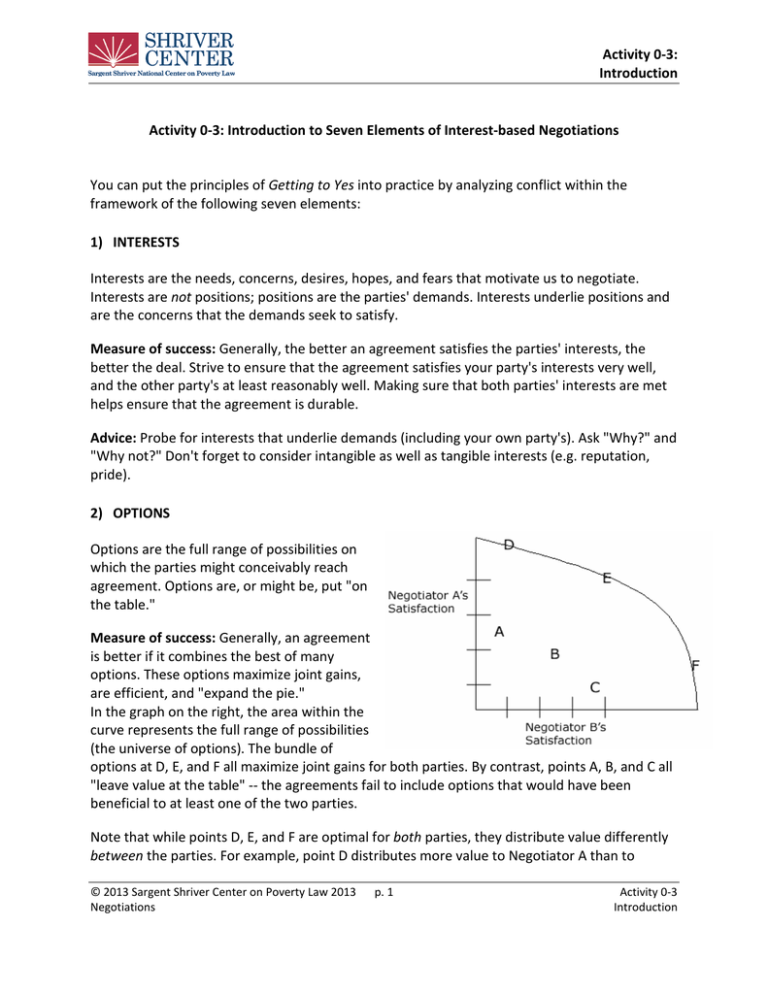

Activity 0-3: Introduction Activity 0-3: Introduction to Seven Elements of Interest-based Negotiations You can put the principles of Getting to Yes into practice by analyzing conflict within the framework of the following seven elements: 1) INTERESTS Interests are the needs, concerns, desires, hopes, and fears that motivate us to negotiate. Interests are not positions; positions are the parties' demands. Interests underlie positions and are the concerns that the demands seek to satisfy. Measure of success: Generally, the better an agreement satisfies the parties' interests, the better the deal. Strive to ensure that the agreement satisfies your party's interests very well, and the other party's at least reasonably well. Making sure that both parties' interests are met helps ensure that the agreement is durable. Advice: Probe for interests that underlie demands (including your own party's). Ask "Why?" and "Why not?" Don't forget to consider intangible as well as tangible interests (e.g. reputation, pride). 2) OPTIONS Options are the full range of possibilities on which the parties might conceivably reach agreement. Options are, or might be, put "on the table." Measure of success: Generally, an agreement is better if it combines the best of many options. These options maximize joint gains, are efficient, and "expand the pie." In the graph on the right, the area within the curve represents the full range of possibilities (the universe of options). The bundle of options at D, E, and F all maximize joint gains for both parties. By contrast, points A, B, and C all "leave value at the table" -- the agreements fail to include options that would have been beneficial to at least one of the two parties. Note that while points D, E, and F are optimal for both parties, they distribute value differently between the parties. For example, point D distributes more value to Negotiator A than to © 2013 Sargent Shriver Center on Poverty Law 2013 Negotiations p. 1 Activity 0-3 Introduction Activity 0-3: Introduction Negotiator B. However, Point D is still better for both parties than point A, although only marginally so for Negotiator B. Advice: You should generate options after discussing interests, and should base the options proposed on these interests. In order to explore value-creating opportunities, follow the general rules of brainstorming: separate the generation of ideas from evaluation and commitment to them. If you are dealing with a negotiator who has trouble with these rules, you might say something like this: "One option might be for me to pay the entire bill; another would be for you to do so. You'd probably prefer one over the other, and I'd probably prefer the opposite. But right now let's focus on coming up with some ideas first and then let's talk about what those options might mean to us." 3) ALTERNATIVES Alternatives are the walk-away possibilities that each party has if it cannot reach an agreement. In general, neither party should agree to something that is worse than its "BATNA" - its Best Alternative To a Negotiated Agreement "away from the table." Measure of success: The negotiated agreement is better than the BATNA. At a minimum, the agreement is better than all other possibilities had you not come to an agreement. Advice: Try to improve your BATNA before beginning the negotiation. For example, if your alternative is to file suit, start drafting the documents for the lawsuit so that your alternative is more palatable. (You may also want to demonstrate this preparation to the other party to make your alternative more credible). You may also consider methods to make the other party's BATNA, to the extent you know or can guess what it is, less appealing. 4) LEGITIMACY Each party in a negotiation wants to feel fairly treated. Measuring fairness by some external benchmark, some criterion or principle beyond the simple will of either party, improves the process. Such external standards of fairness include laws and regulations, industry standards, current practice, and some general principle such as reciprocity or precedent. Some possible sources of legitimacy include: • Law: Code, regulation, court / administrative procedure • Practice: Prevailing norms, professional opinion, historical precedent, tradition • Value: Market value, replacement value © 2013 Sargent Shriver Center on Poverty Law 2013 Negotiations p. 2 Activity 0-3 Introduction Activity 0-3: Introduction • Morality: Community, cultural, religious values – be sure to specify whose • Process: Equality, reciprocity, expediency Measure of success: Select criteria such that no party feels taken. Of course, you generally want standards of legitimacy that favor your particular interests. Advice: You can use standards as a "sword": "Let me show you why this is fair." You may also use it as a "shield": "Why is that a fair number?" 5) RELATIONSHIP Most important negotiations are with people or institutions with whom we have negotiated before and will negotiate again. In general, a strong working relationship empowers the parties to deal well with their differences. Any transaction should improve, rather than damage, the parties' ability to work together again. Measure of success: As a result of the negotiation, the relationship improves or, at minimum, is not harmed. Advice: Be unconditionally constructive in the relationship. Separate the people from the problem. Speak for yourself, not for them. 6) COMMUNICATION Communication is the exchange of thoughts, messages, or information by speech, writing, physical cues, or other actions. It is through communication that you can convey or discover the other elements of this framework. Measure of success: The message sent is the message received. Good communication improves, or at least doesn't damage, the relationship with the other party. Advice: Remember, both in terms of your conveyance to the other party as well as your understanding of the other party, to separate the impact from the intent of an effort at communication. (Consider the phrase, "That's not what I meant!") Therefore, tailor your words and tone to the needs of your intended audience, but also be sure to check your understanding with the other party through active listening ("You expressed X; is that correct?"). Combine your advocacy with plenty of inquiry. 7) COMMITMENTS © 2013 Sargent Shriver Center on Poverty Law 2013 Negotiations p. 3 Activity 0-3 Introduction Activity 0-3: Introduction Commitments are oral or written statements about what a party will or won't do. They may be made during the course of a negotiation or may be embodied in an agreement reached at the end of the negotiation. Measure of success: In general, an agreement will be better to the extent that the promises made have been well planned and well-crafted so that they will be practical, durable, easily understood by those who are to carry them out, and verifiable and enforcable if necessary. They should encompass the questions, "Who will do what by when, and what will happen if they don't?" Advice: Beware of committing too early to an agreement. Make sure you know exactly what both they and you are committing to, and that you share a common understanding of this commitment. 4820-4016-3603, v. 1 © 2013 Sargent Shriver Center on Poverty Law 2013 Negotiations p. 4 Activity 0-3 Introduction