Maintaining and improving quality from April 2013

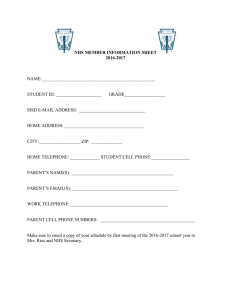

advertisement