Managing Upward and Downward Accountability in an International

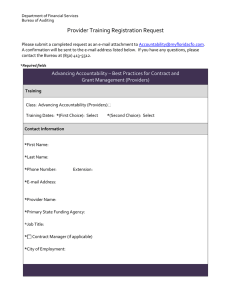

advertisement