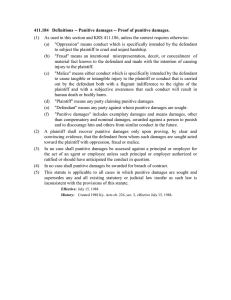

Louisiana Punitive Damages

advertisement