James Service`s House - City of Port Phillip

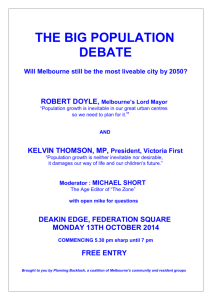

advertisement

1 James Service’s House Between 1854 and 1862 the two-storey timber house at 337 Dorcas Street, South Melbourne, was the private residence of James Service (1823-1899). In 1855 Service became the first chairman of the Emerald Hill Town Council (South Melbourne’s former name), and in 1880 went on to become Premier of Victoria, a position he held again from 1883-1886. Also a prominent businessman, James Service established a general import business soon after his arrival in Victoria in 1853. He went on to become a founder of the Commercial Bank of Australia in 1866, and to play a significant role in the foundation of the Alfred hospital in 1868-1870. The two-storey timber abode at 337 Dorcas Street, South Melbourne, was the private residence of James Service (1823-1899) during the early years of his political career. Service arrived in the new colony with his wife and two daughters aboard the Abdallah in July 1853. The family’s first few weeks were spent in Canvas Town before moving to Emerald Hill. In the mid 1850s the timber house in Dorcas Street was one of the larger dwellings in Emerald Hill, boasting ‘seven rooms, a kitchen, stables, coach house, and a garden’.1 In 1856 it was valued at sixty pounds. The house stands today much as it did in the nineteenth century, the main exception being the two-storey verandah which has been altered. From the time of his arrival in Victoria James Service resided in the South Melbourne and St Kilda area (both now part of the City of Port Phillip). By the mid 1860s he had moved to St Kilda, and in 1871 moved into a grand twelve room house in Carlisle Street, St Kilda named ‘Kilwinning’ in honour of his birthplace in Scotland. It was in this house that he spent the last days before his death in 1899. James Service was a prominent and well regarded citizen of Emerald Hill. Originally from Aryshire, Scotland, Service had been a school teacher prior to emigrating to Australia. James’ father, Robert Service, was a zealous preacher of the Churches of Christ, having been converted from Presbyterianism by the Baptists.2 James’ inquiring mind, however, led him down the path of scepticism and, despite his father’s beliefs, he eventually lost faith in organised religion. Service abandoned teaching following a bout of tuberculosis in 1845, and in 1846 joined the coffee and tea business of Thomas Corbett 1 2 Susan Priestley, South Melbourne: A History (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 1995), 54. Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol. 6, p. 106. 2 & Co. It was as an agent for this company that James Service arrived in Victoria in 1853, however, he soon found occasion to pursue his own business interests and established an import concern in 1854. While business always played a role in James Service’s life, politics rapidly came to dominate his career. Service became the most prominent leader in the Emerald Hill campaign for emancipation from the Melbourne City Council soon after his arrival in the colony. The success of this campaign, which made Emerald Hill the first of Melbourne’s suburbs to adopt full municipal status, led to his becoming the first Chairman of the Emerald Hill Town Council in 1855. Following the secession of Emerald Hill from Melbourne, the City Council claimed that it was entitled to collect rates from homeowners for the year 1855 because the proclamation of independence had been issued ten days after the date rates became due.3 This was received with much anger and disgust on the part of the Hill residents who, under the direction of Service and other prominent citizens, launched a campaign of civil disobedience and refused to pay the Melbourne rates. James Service’s house became the site of one of the most venerated victories of this campaign against the Melbourne City Council, when during his absence the bailiffs were sent to his residence to remove his furniture as payment for the outstanding rates. A group of local residents took action by ringing the fire bell and successfully barring the bailiffs from entering Service’s house.4 On another occasion Service fought to save Emerald Hill from a particular kind of ‘inappropriate development’. For some months in 1857 the Melbourne and Hobson’s Bay Railway Company threatened to build a line through Emerald Hill to St Kilda which would have effectively cut the town in half and leave it without a station. The company commenced excavation work in Coventry Street without a permit and erected a fence across the street. This action angered Service and the other Councillors who responded by legally placing obstructions in the way and threatening to have anyone arrested who removed them. Service’s direct action enabled the Emerald Hill Council to get its point across and the construction of the railway line proceeded with more respect for the interests of the residents. 3 4 Priestley, South Melbourne: A History, 60. Ibid., 60-61., and Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol. 6, p. 106. 3 Politically, James Service was known as a ‘red-hot Chartist radical’.5 Chartism was a platform for English political reform and supported universal (male) suffrage. Service certainly espoused this belief. He was also an avid ‘free-trader’, yet despite the strong conservatism that came to dominate this stance, Service remained a moderate throughout his political career. In fact, much of his political success has been attributed to his refusal to ‘go conservative’.6 A classic liberal, Service strongly supported the separation of church and state. This stance pitted many Catholic voters against him. He was generally democratic in outlook, materially supportive of trade unionism, early shop closing and the eight hour day. He also claimed to advocate amity between the classes. Service’s first term as Premier was largely unsuccessful, but his second was a great achievement. His accomplishments included the reformation of the civil service and the railways, the Factories Act and the legalisation of Trade Unions. He is most renowned, however, for his efforts to unite the colonies under a federal union. Unfortunately, he did not live quite long enough to see this come about. His business and community interests were extensive. He was a founder of the Commercial Bank of Australia in 1866, and played a fundamental role in the foundation of the Alfred Hospital in 1868-70. James Service enjoyed much popularity as a politician, despite his unusual domestic arrangement and secularist orientation. Service had left his wife, Marian Allan, and their two daughters in the late 1850s, and in the early 1860s began cohabiting with Louisa Hoseason Forty. The couple had several daughters together but never married. Service seems to have successfully avoided the social stigma that a person of prominence living such a lifestyle in the Victorian era would have attracted. This may be taken as an indication of the high regard in which he was held for his contribution to politics, business and the welfare of the citizens of Victoria. Further Reading City of Port Phillip. Port Phillip Heritage Review (version 2) [CD Rom]. Port Phillip Planning Scheme, 2000 [cited 2002]. Priestley, Susan. South Melbourne: A History. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 1995. 5 6 Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol. 6, p. 107. Ibid., p. 108. 4 Serle, Geoffrey. Entry for “Service, James” in Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol. 6, pp. 106-112.