Discussion Paper - Reform of the Federation White Paper

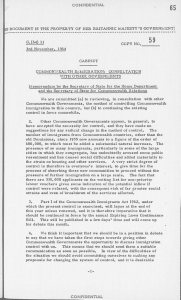

advertisement