Court - Opinions, Nonprecedential Dispositive Orders and Oral

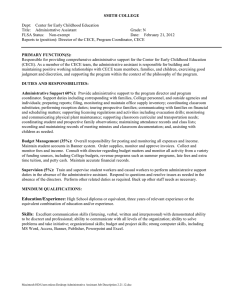

advertisement