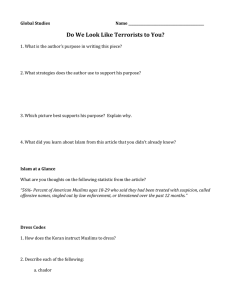

a report on converts to islam

advertisement