Explaining Clearly

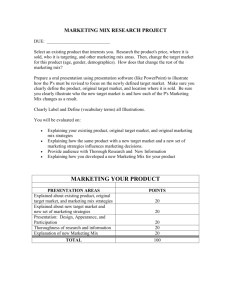

advertisement

14 Explaining Clearly Before launching into an explanation, give your students the context, struc­

ture, and terminology they will need to understand the new concept and to

relate it to what they alre~ldy know. Use repetition and examples to help them

focus on the essential points. Try to refrain from introducing too many ne\N

concepts at the same time.

General Strategies

Place the concept in the larger context of the course. To give students a

sense of continuity and meaning, tell them how today's topic relates to earlier

material. A brief enthusiastic summary will help the class see the relevance of

the new concept and its relationship to the course's m,lin themes.

Give students a road map. You don't want students spending the hour

wondering, Why is the professor talking about that? or Where does this fit

in? So, at the beginning of

put a brief outline on the board or provide a

handout that will help students follmv along. Refer to the outline to alert

students to transitions and to the relationships between points. Some faculty

give students a list of questions to be addressed during the class. Handouts

can also include new terms, complex equations, formulas, and copies of

detailed overhead transparencies or slides shown in class.

Avoid telling students everything you know. Students become confused,

105t, anxious, or bored when inundated with information. Be selective:

deliver the most essential information in m,mage,lble chunks.

Set an appropriate pace. Tllk more slowly when students are taking notes

and when you are explaining new matenal, complex topics, or abstract

issues. You can pick up the pace \vhen relating stories, summarizing a

previous lecture, or presenting an example.

Aiding Students' Comprehension

Don't make assumptions about what students know. Define not only

technical terms but also unusual words or expressions, and review ke., terms

120

Explaining Clearly

from previous lectures. Introduce new terms one at a time, and write each on

the board.

Acknowledge the difficulty of concepts students are likely to find hard

to understand. Cue students to the most difficult ideas by saying, "Almost

everyone has difficulty with this one, so listen closely." Because the level of

students' attention varies throughout the hour, it is important to get everyone

listening carefully before explaining a difficult point.

Create a sense of order for the listener. In written texts, organization is

indicated by paragraphs and headings. In lectures, your voice must convey

the structure of your lectures. Use verbal cues to do the following:

• Forecast what you will be discussing: "Today I want to discuss three

reasons why States dre mandating assessments of student learning in

higher education."

• Indicate where you are in the development of your ideas: "The first

reason, then, is the decline of funds available for social and educational

programs. Let's look at the second reason: old-fashioned politics."

• Restate main ideas: "We've looked at the three pressures on colleges and

universities to institute assessment procedures: the legislature'S desire to

get maximum effectiveness for limited dollars, the appeal of campaign

slogans such as 'better education,' and public disenchantment with

education in general. We've also explored two possible responses by

colleges and universities: compliance and confrontation."

Begin with general statements followed by specific examples. Research

shows that students generally remember

or principles if they are pre­

sented first with a concise statement of the general rule and then with specific

examples, illustrations, or applications (Bligh, 1971; Knapper, 1981). To

present a difficult or abstract idea, experienced faculty recommend that you

first give students an easy example that illustrates the principle, then provide

the general statement and explanation of the principle, then offer a more

complex example or illustration. finally, address any qualifications or elab­

orations. (Source: Brown, 1978)

Move from the simple to complex, the familiar to unfamiliar. Layout the

most basic ideas first and then introduce complexities. Start with what

students know and then move to new territory.

121

TOOLS FOR TEACHING

Presenting Key Points and Examples

Limit the number of points you make in a single lecture. Research shows

that students can absorb only three to five points in a fifty-minute period and

four to five points in a seventy-five-minute class (Lowman, 1984). Even the

most attentive students retain only small quantities of new information

(Knapper, 1981). Be ruthless in paring down the number of major points you

make, and be more generous with examples and illustrations to prove and

clarify your arguments. Cut entire topics rather than condense each one. As

necessary, supplement your lecture with a handout that students can study

for a more detailed treatment.

In introductory courses, avoid the intricacies of the diSCipline. To avoid

confusing a class of beginning undergraduate students, focus on the funda­

mentals, use generalizations, and do not give too many exceptions to the

rule.

Demonstrate a complex concept rather than simply describe it. For

example, instead of telling students how to present a logical argument,

present a logical argument and help them analyze it. Instead of describing

how to solve a problem, solve it on the board and label the steps as you go

along.

Use memorable examples. Vivid examples will help students understand

and recall the material. Spend time developing a repertoire of examples that

link ideas and images. Use examples that do the following (adapted from

Bernstein, n.d., pp. 27-28);

• Draw upon your students' experiences or are relevant to their lives (to

explain depreciation, a professor uses the drop in prices of new versus

used textbooks)

• Represent the same phenomena (to explain aerodynamic oscillation,

an instructor cites a scarf held out a window of a moving car, a thin

piece of paper placed near an air conditioner, and a suspension bridge

battered by gale winds)

• Dramatize concepts (in defining a particular body organ, a professor

compares its size or texture to familiar objects, such as a walnut or

grapefruit; an economics professor defines a trillion by saying, "It takes

31,700 years to count a trillion seconds. ")

• Engage students' empathy ("Imagine yourself as Hamlet. How does the

poison feel? How does it affect your speech?")

122

Explaining Clearly

Liberally use metaphors, analogies, anecdotes, and vivid images.

Students tend to remember

longer than they remember words

(Lowman, 1984). You can help students recall important concepts by pair­

ing abstract content with a vivid Image or a concrete association. For

example, in describing velocity a physics professor uses the example of a

speeding bullet.

Call attention to the most important points. Your students may not grasp

the importance of a point unless you announce it: "This is really important,

so listen up" or "The most important thing to remember is ... "or "This is so

important that everyone of you should have it engraved on a plaque hung

over your bed" or "You don't have to remember everything in this course, but

you should remember ... "or "This is something you will use so mdny times

that it\ worth your special attention." It is also useful to follow through by

explaining why a particular point is important-saying so may not be

enough.

Using Repetition to Your Advantage

Stress important material through repetition. Students' attention wan­

ders during class. Indeed, research suggests that students are focally avvare of

the lecture content only about SO to 60 percent of the time. To underscore the

importance of a point, you will need to say it more than once. (Source:

Pollio, 1984)

Use different words to make the same point. No single explanation will

be clear to all students. By repeating major points several times in different

words, you maximize the chances that every student \vill eventually under­

stand. In some disciplines you may be able to develop the same point ill two

or three different modes: mathematically, verbally, graphically. [n others, )OU

may v.. ant to say things twice: formally and colloquiall}.

Use redundancy to let students catch up with the material. Students will

if they are :,till grappling with the

have trouble understanding a second

first. Give student, a chance to catch up bv building in redundancy, rcpeti­

tion, ,md pauses.

References

Bernstein, H. R. M,mualjm 7i'ar:hing. Ithaca, N. Y.: Center for the Improvc­

ment of Undergraduate Education, Cornell University, n.d.

123

TOOLS FOR TEACHING

Bligh, D. A. What's the Use otLecturing? Devon, England: Teaching Services

Centre, University of Exeter, 1971.

Brown, G. Lecturing and ExpLaining. New York: Methuen, 1978.

Knapper, C. K. "Presenting and Public Speaking." In M. Argyle (ed.), Social

Skills and \X/ark. Kew )'iJrk: Methuen, 1981.

Lowman, J. Mastering the Techniques of Teachinl{. San Francisco: Jossey­

Bass, 1984.

Pollio, H. R. "What Students Think About and Do in College Lecture

Classes." Teaching-Learninl{ Issues] 984,3,3-18. (Publication available

from the Learning Research Center, University of Tennessee, Knoxville)

124