By eliminating seldom-used pathways the brain leaves room for

advertisement

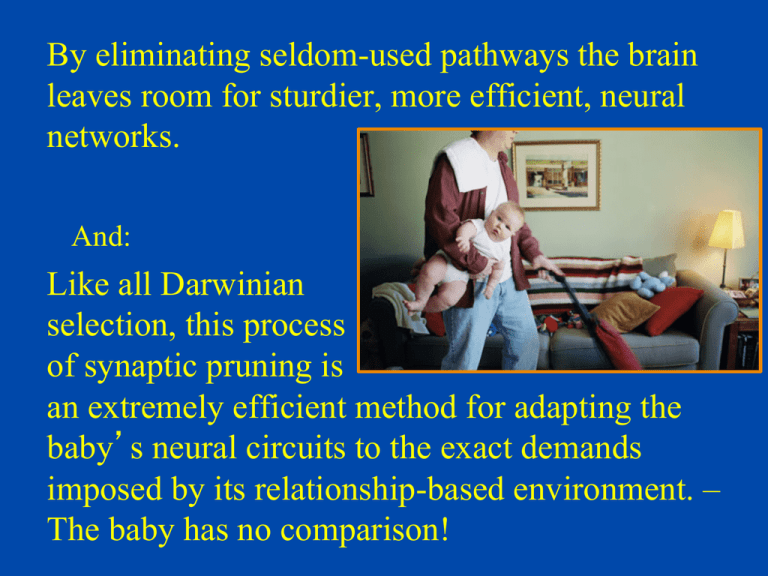

By eliminating seldom-used pathways the brain leaves room for sturdier, more efficient, neural networks. And: Like all Darwinian selection, this process of synaptic pruning is an extremely efficient method for adapting the baby’s neural circuits to the exact demands imposed by its relationship-based environment. – The baby has no comparison! Plus experience-dependant plasticity. Our nervous system forms in an ecological dialogue with our physical and social environment. The brain creates, strengthens and discards synapses and neuronal pathways in response to the environment. In later years it organises itself in a ‘use-dependant’ fashion, where growth is initiated by the unique experience of the individual. A matter of inspire and rewire! Synaptogenesis occurs in those brain regions involved in processing particular events. “Plasticity is a double-edged sword that leads to both adaptation and vulnerability. (p.94) Neurons to Neighborhoods. What about attachment? Attachment is an example of a developmental progression that is particularly sensitive to the environment since “the formation of an attachment may reflect an experienceexpectant process but the quality of the attachment may reflect an experience-dependant process. A child whose caregivers respond consistently and sensitively during the infancy period is more likely to become a psychologically well-functioning adult, capable of forming lasting relationships with others. A child who grows up in an institution where ‘caregiving’ largely consists of being fed and changed is far less likely to attain psychological health.” (p. 302) Nelson, C. A., Fox, N. A. & Zeanah, C. H. (2014) Romania’s Abandoned Children. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. Sensitive periods. The central nervous system requires ‘instruction’ from experience during sensitive periods in order to develop properly. Sensitive periods in the development of complex behaviors reflect sensitive periods in the development of the neural circuitry that underlies these behaviors. Such periods allow experience to instruct neural circuits to process or represent information in a way that is adaptive for the individual in that particular environment. The effects of experience will operate within the constraints imposed by genes on a circuit. Neural networks in different areas of the brain associated with specific functions proliferate rapidly and then begin pruning in the earliest years of life. Windows of opportunity. Birth to 6 months old. Brain growth is unmatched during the first six months of life. The most critical windows during this stage are vision, vocabulary, and emotional development. Because the windows for vision and emotions begin to shut so early, it is important to pay attention to them during this stage. 6 to 12 months old. With connections primarily established for sight, the critical windows during this stage are speech and emotional development. The foundations for governing emotions are established. Language capacity grows tremendously during this period, and this is a good time to introduce the natural sounds of other languages. 12 to 18 months old. Most of the critical windows of human brain development are open during this stage. At no other time is the brain so receptive and responsive. Many of the neurological connections that govern a lifetime of skill and potential are beginning to take shape. 18 to 24 months old. Children in this stage are gaining more control of their bodies, and their motor skills are developing. They are becoming more aware of other people’s feelings and beginning to learn to share. Language and vocabulary remain important. Attention should be given to how maths and logic are discovered through play as well – preferably outdoors. 2 to 3 years old. By the age of three, much of a child’s brain growth and density is complete. The brain patterns that will guide a child’s development are already well established. The critical windows for some skills such as speech begin to close, so vocabulary building - the sound of speech - is important. Brain patterns for music begin to develop at the end of this stage. 3 to 5 years old. Between the ages of three and five, most of the remaining critical windows in a child’s brain development begin to close. There appears to be a connection between the brain patterns stimulated by music and the part of the brain used to understand spatial concepts in math. The brain patterns created while learning a musical instrument between ages 3 and 10 are hard-wired for life. But sometimes things go badly wrong. The small child’s environment is defined by relationships. Neglect is the absence of critical relationship-based organising experiences at key times during development. e.g. post-natal depression, household with violence, parents who themselves were ‘looked after’. “During brain growth there is a constant sorting and juggling of nerve cells and connections. Those that make a match with their environment thrive, and the others wither.” (p.124.) And so: “Impoverished environments appear to have the opposite effect of rich and varied surroundings. They suppress brain development.” (p. 158) Bownds, M. D. (1999) The Biology of the Mind. Bethseda: Fitzgerald Science Press. Windows of vulnerability. P.E.T. scan of a normal two year old. The temporal lobes receive and integrate inputs from the senses, and combine them with deep primitive drives from the limbic system and brain stem. They also deal with hearing, learning, memory skills, emotions and identifying familiar and trustworthy people. PET scan of the brain of a Romanian orphan institutionalised shortly after birth shows the effects of extreme deprivation in infancy. Global neglect has been followed by atrophy of ‘unnecessary’ areas. For a direct comparison. Normal 2-year old. 2-year orphan. The neurobiological impact of maltreatment. “Because childhood abuse occurs during the critical formative time when the brain is being physically sculpted by experience, the impact of severe stress can leave an indelible imprint on its structure and function. Such abuse, it seems, induces a cascade of molecular and neurobiological effects that irreversibly alter neural development.” (p.56) Martin H. Teicher. Scars that won’t heal: the neurobiology of child abuse. Scientific American, March 2002. pp.54-61. • The organising brain requires patterns of sensory and emotional experience to create the patterns of neural activity that will guide the neurobiological processes involved in development. • In the face of interpersonal trauma, all the systems of the social brain become shaped for offensive and defensive purposes. • A child growing up surrounded by trauma and unpredictability will only be able to develop neural systems and functional capabilities that reflect this disorganisation. The orbitofrontal cortex and trauma. The orbitofrontal cortex is the brain system involved in social adjustment, the control of mood, drive and responsibility and those traits that are seen to define the personality of an individual. It is the site of the attachment control system, and makes sense of the reactions triggered by the amygdala. This is the only area of the brain that is one synapse away from the cortex, limbic structures and brain stem, and so integrates them into a functional whole. The orbitofrontal cortex begins its critical period of growth from the last quarter of the first year to the end of the second. Relational trauma at this time interferes with the organisation of orbitofrontal regions, which are responsible for regulating the autonomic nervous system (ANS). It is also involved in the regulation of emotion and intersubjectivity; and is crucial to the development of moral behaviour. Trauma will compromise such functions as attachment, empathy, the capacity to play and affect regulation. An inefficient right orbitofrontal system will be unable to modulate the response of the amygdala to emotionally significant and stressful stimuli, e.g. an interpersonal threat, a sense of defeat or a feeling of shame. Hypothalamus controls autonomic nervous system through pituitary gland & adrenal cortex. Orbital-frontal cortex The HPA axis is programmed by early caregiving behaviour. Linking thalamus, amygdala and cortex. Prefrontal cortex. (The slow, thoughtful, track.) Hippocampus. Busy translating the sight of danger into preparing to fight, flee or freeze. Sensory gateway to cognitive processes organised through cortex and hippocampus. This contextualises and makes sense of Thalamus. experience. (The fast, primitive, track.) Perception. Here we have the evaluation of experience and the regulation of emotions by cognitive processes. Amygdala. Reflexive activation of emotions and defences before cognitive processes in the pre frontal cortex occur. Controls emotional and physical responses. “Abuse and neglect in the first years of life have a particularly pervasive impact. Pre-natal development and the first two years are the time when the genetic, organic, and neurochemical foundations for impulse control are being created. It is also the time when the capacities for rational thinking and sensitivity to other people are being rooted - or not - in the child’s personality.” (p. 45) Karr- Morse, R. & Wiley, M. (1997) Ghosts From the Nursery. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press. Early experiences of prolonged and frequent trauma in the form of episodes of intense and unregulated stress within the family may be deemed ‘toxic’; and in babies and toddlers this may have devastating effects on the establishment of psycho-physiological regulation and the establishment of stable and trusting relationships in future life. This will also influence how and when the child, and later the adult, responds to real or perceived threats. . This is neuro-hormonal programming for survival. Pathway to the stress response. Sensitive Secure attachment / resilience. Return to caregiver calm state. Affect regulation occurs. response. Fight or flight, Signal of threat, hyperarousal. hostile or Survive by action. helpless caregiver, sense of fear, feeling No response. abandoned, An inappropriate inappropriate response. responses from Freeze & fade. ‘scaregiver’, etc. The infant is making ‘Terror without solution’ a bid for interactive Dissociation, or hypoarousal. regulation. Crying is Survive by disappearing. an attachment signal. The two opposite neurochemical response patterns to threat. (1) The hyperarousal continuum: this comprises the defensive ‘fight or flight’ responses, expending bodily resources for survival. The initial stages of threat trigger the sympathetic system’s alarm reaction, stimulating the brain stem to release adrenalin and noradrenalin which then trigger the release of glucose and insulin. The body is now on alert and high arousal. If the threat materialises then the full fight or flight response becomes fully activated via the HPA axis. Inescapable threat within the familyis a form of toxic stress. Thus the components of the fear response become sensitised, putting the child in a persisting fear state (a state becomes a trait) that causes exaggerated reactivity. He or she may become hyperactive, over-sensitive and hypervigilant, and move quickly from anxiety to terror. This may cause persistent hyperarousal disorders such as ADHD, PTSD and conduct disorders. It also negates the capacity for rational thought. Cortisol is a steroid hormone that is released in response to stress, generating new energy from stored reserves, diverting energy from low-priority functions such as the auto-immune system, and sparing available glucose for the brain. Elevated levels break down proteins and increase blood pressure. It suppresses the immune system, inhibits physical growth, and affects many aspects of brain functioning including emotions and memory. It is toxic to growing brain cells. It is also released when the baby experiences a lack of stimulation & touch. The ‘antidote’ is oxytocin and laughter! Scared stiff! • Extreme, inescapable, terror halts normal metabolism. Energy is conserved by passive withdrawal. • If ‘flight or flight’ is not an option for immediate survival, and nothing will reduce the threat, the dorsal vagal mechanism kicks in. • This is the most primitive reaction system; it activates an ‘end-of-theline’, play dead or die, parasympathetic response. (2) The dissociative continuum: The parasympathetic system is normally the ‘rest and digest’ branch of the ANS, concerned with selfmaintenance, conserving bodily resources and building energy. When over-activated in order to disconnect from a horrific reality, it leads to a ‘freezing’ reaction that slows the heart and breathing, shutting down the body rather than mobilising it. The child is rigid with fear, but may remain hypervigilant. Babies and toddlers can neither fight nor flee. In the stage of early alarm, when the attachment system is activated, the infant can only use a limited repertoire of behaviour to attract the attention of the caregiver. If this strategy is ineffective, so there is no soothing response from a caregiver, the child will abandon the early alarm signal which will then be extinguished. The attachment cry becomes a futile gesture. Such a defeat response of ‘learned helplessness’ is common in neglected and abused children and adults. In the face of persisting threat the only ‘escape’ may be to dissociate and physically and cognitively freeze. (Play dead.) Such mental mechanisms of defence involve disengaging from the external world and only attending to stimuli from the internal world, thus becoming disconnected from reality. Again a state may become a trait. Stress! Sensitive caregiver. Homeostatic recovery. Heightened arousal. States Traits Infant learns to tolerate internal challenges. Calm & connect versus flight, fight or freeze. Super nanny! Insensitive caregiver. Dysregulated stress response. Under or over activity becomes a hard-wired feature of stress response system. Trauma in infancy - abusive parenting, toxic stress, attachment system compromised, emotional dysregulation, hopelessness, chronic fearful arousal, lack of basic trust, disorganisation. Sensitised nervous system as brain adapts to emotional environment. Stress in adult: maladaptive coping strategies, reminders and experiences of trauma, adverse life events, relational aggression, etc. Permanent psychological distress - conscious or unconscious, lack of reflection, unbearably painful emotional states, low self-esteem. Retreat as self-protection: isolation and loneliness, dissociation, depression. Self-damaging actions: substance abuse, eating disorders, deliberate self-harm, suicidal actions. Destructive actions: aggression, violence, fundamentalism, rage, crime. Implications for babies. Optimal growth and development occurs within nurturing relationships; and these directly affect the formation of neural networks and the capacity for emotional-regulation. The birth and care of a baby offers a (new) chance for change. All parents want to do the best they can for their babies. But not all parents have the same resources. Recommended reading. For an overall view Sue Gerhardt, (2015) Why Love Matters (2nd Ed.) A focus on teenagers – Daniel Siegel, (2013) Brainstorm: The Power and Purpose of the Teenage Brain. See this important report from the D of E and the WAVE Trust. http:// www.wavetrust.org Plus the ‘The 1001 Critical Days’ manifesto on http://www.pipuk.org.uk Association of Infant Mental Health (UK). This is an organisation for those interested in all branches of infant development as well as early intervention with babies and their families. It goes with reduced rates at their workshops and conferences, with access to a lot of information on the website. Group membership for Children’s Centres. Application forms from: Administrator AIMH(UK). email: info@aimh.org.uk website: www.aimh.org.uk Our advisory panel.