ETHNIC ORIGIN AND DISABILITY DATA COLLECTION IN EUROPE

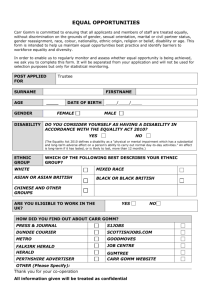

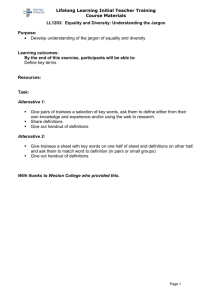

advertisement