Impacts of Active Labor Market Programs

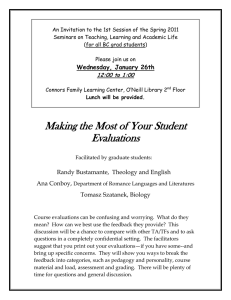

advertisement