Three Reasons to Register Your Copyrights By Cory L. Webster, Esq

advertisement

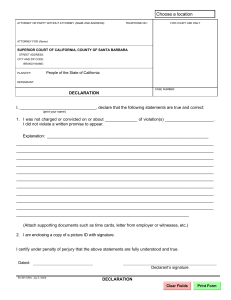

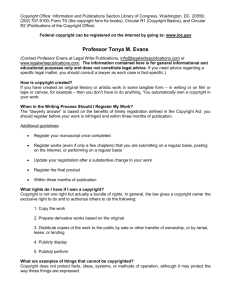

Three Reasons to Register Your Copyrights By Cory L. Webster, Esq. Copyright registration is a fairly straightforward procedure. It is accomplished by delivering to the Copyright Office an application form, fee, and copy of the work being registered. 17 U.S.C. § 408(a). Yet, for whatever reason, authors and owners of copyrights often forgo registration. Copyright holders can hardly be blamed for mistakenly believing their works have full copyright protection without having obtained registration with the Copyright Office. Under the 1909 Copyright Act, observing certain formalities, including registration, was mandatory to receive copyright protection. If the author failed to register, the work would enter the public domain. However, the 1976 Copyright Act and the United States’ adoption of the Berne Convention in 1988 did away with many of the strict formalities associated with copyright protection. The 1976 Copyright Act specifically provides that registration is “permissive” and that “registration is not a condition of copyright protection.” 17 U.S.C. § 408(a). “[C]opyright automatically inheres in the work at the moment it is created without regard to whether it is ever registered.” Montgomery v. Noga, 168 F.3d 1282, 1288 (11th Cir. 1999). From all this, one could get the impression that registration is unnecessary for preservation of copyright protection. However, even though it removed many of the formal requirements for copyright protection, Congress included in the 1976 Copyright Act a number of “incentives” to encourage registration. 1. Registration is a prerequisite to a copyright infringement action. One of these incentives is that registration is a prerequisite to a copyright infringement action. 17 U.S.C. § 411. Although registration is not a condition of copyright protection, a copyright cannot be enforced unless the author registered the work (with a few narrow exceptions). In a very real 1|Page The author, Cory L. Webster, Esq., is an attorney with Enterprise Counsel Group, ALC. Mr. Webster's practice focuses on business litigation and appellate matters. way, creating an original work without registering it gives an author a “right without a remedy.” A copyright holder who waits to register until after discovering infringement can only get actual damages and the defendant’s profits attributable to infringement. 2. Statutory damages and attorney’s fees are generally not available without registration. Second, a copyright holder who waits to register until after discovering infringement will lose out on important remedies. The Copyright Act authorizes a court to award statutory damages and attorney’s fees to a prevailing copyright infringement plaintiff. 17 U.S.C. §§ 504, 505. For “innocent” infringement, statutory damages of up to $30,000 may be awarded for each work infringed. A plaintiff who can show the “infringement was committed willfully” can receive up to $150,000 in statutory damages per work. Additionally, “an award of attorney’s fees to a prevailing [party] that furthers the underlying purposes of the Copyright Act is reposed in the sound discretion of the district courts . . . .” Fantasy, Inc. v. Fogerty, 94 F.3d 553, 555 (9th Cir. 1996). As for the government filing a federal criminal action, thus far copyright registration is not a prerequisite, United States v. Wittich, F. Supp. 3d 613, 629 (E.D. La. 2014), although this matter has not seemed to garner the interest of the federal appellate courts. However, statutory damages and attorney’s fees (with a few narrow exceptions) are not available if the work is not registered before the defendant begins infringement. 17 U.S.C. § 412. In other words, if an infringer started selling an infringing product before the plaintiff obtained registration, the plaintiff cannot obtain statutory damages or attorney’s fees, even if the infringer continues to sell the infringing product long after registration. In such a case, the plaintiff can only receive actual damages and the defendant’s profits attributable to infringement. 3. Timely registration constitutes prima facie evidence of copyright validity. Third, a copyright plaintiff gains an evidentiary advantage by timely registration. 17 U.S.C. § 410(c). One of the two elements of a copyright infringement claim is “ownership of a valid copyright.” Feist Publications, Inc. v. Rural Tel. Serv. Co., 499 U.S. 340, 361 (1991). Obtaining registration within five years of first publication of a work constitutes prima facie evidence of the validity of the copyright and of the facts stated in the certificate. This shifts the burden to the defendant to disprove copyright validity. Moreover, even if a work is registered more than five years after first publication, the court still has discretion to give evidentiary weight to a certificate of registration. Although the formalities of copyright law have been liberalized, copyright holders should be aware of the rights they risk losing when they fail to register their copyrights. Provisions in 2|Page The author, Cory L. Webster, Esq., is an attorney with Enterprise Counsel Group, ALC. Mr. Webster's practice focuses on business litigation and appellate matters. the Copyright Act relating to registration put in perspective—if not dispel—the misnomer that “registration is not a condition of copyright protection.” To ensure you do not lose valuable rights, register your copyright. The process of registration is fairly simple and relatively inexpensive. Better to be safe than sorry. This article was written for informational purposes only and not for the purpose of providing legal advice. You should contact an attorney to obtain advice with respect to any particular issue or problem. 3|Page The author, Cory L. Webster, Esq., is an attorney with Enterprise Counsel Group, ALC. Mr. Webster's practice focuses on business litigation and appellate matters.