The Adolescent Diversion Program

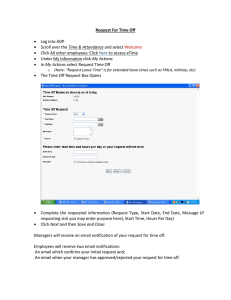

advertisement