FIRST LOOKS SECOND LOOKS RED AND ORANGE STREAK

advertisement

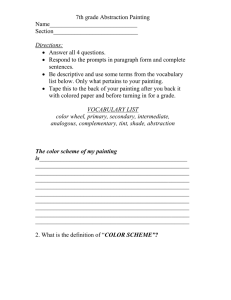

RED AND ORANGE STREAK What is happening in this dark painting? Two wide bands of orange curve up from the lower left, then shoot out of the painting at the upper right. In between them, a yellow Z shape is placed at an angle. It catches our eye because it is so bright against the dark 1919 Oil on canvas 27 x 23 inches (68.6 x 58.4 cm) GEORGIA O’KEEFFE American Bequest of Georgia O’Keeffe for the Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1987, 1987-70-3 FIRST LOOKS What is the brightest color in this painting? What is the darkest? What shapes do you see? Do they appear to be still or moving? How can you tell? Which one could be the horizon? Which ones looks like letters of the alphabet? Where could this be? What time of day? Why? What do you think is happening? background and it seems to be moving! Behind, a strip of dark red extends quietly from one side of the painting to the other, like a horizon line. Look how the orange arcs and the red band form a cross with four arms that stretch out into the darkness and touch three sides of the canvas. The focal point of the painting is the angular, yellow form that overlaps the red band and the black background. Georgia O’Keeffe painted Red and Orange Streak in 1919, soon after she moved from Texas to New York City. She had been greatly impressed by the wide-open plains of Texas, especially at night when she took long walks by herself. In the pitch-black darkness, certain sounds like a train whistle or cattle lowing for their calves suggested shapes and colors to her. Storms, which can be seen approaching from far away in the flat Texas landscape, also fascinated her. The sky was like an enormous canvas, and the lightning appeared to be giant, jagged writing scrawled across it, just for an instant. In a letter to a friend, O’Keeffe wrote: “the whole thing—lit up—first in one place—then in another with flashes of lightning—sometimes just sheet lightning—and sometimes sheet lightning with a sharp bright SECOND LOOKS What part of the painting seems closest? Most far away? Where is the focal point, the part your eye is most drawn to? Why? Find some places where the colors blend gradually. Where are they separated by clean edges? What sounds do you think of when you look at this painting? Why? zigzag flashing across—I . . . sat on the fence for a long time—just looking at the lightning.” Back in New York City, O’Keeffe remembered the natural world that had surrounded her in Texas and she wanted to express her intense responses to that environment. She did this by abstracting, or simplifying, what she had seen, heard, and felt there and by eliminating details. Some of her shapes suggest solid forms while others Education | seem more like empty spaces. Look at the long, pointed spaces between the orange arcs—one thrusting upwards, the other downwards. How do they make you feel? Notice how some of the edges between colors are crisp and clean, while others blend and blur. In the background, the horizontal band of red has just enough modeling (light and dark areas that show three-dimensional form) to suggest a mountain range in the distance. Georgia O’Keeffe’s dramatic painting, based on her vivid memories of Texas, exists on the edge of abstraction, inviting us to experience it in our own ways. ABOUT THIS ARTIST Georgia O’Keeffe was born in Sun Prairie, Wisconsin, to an Irish father and a Dutch-Hungarian mother in 1887. The second of seven children, she lived on her family’s large farm until she was fifteen years old. She came from a family of independent women. Her grandmothers were frontier wives who raised their families alone. She also had two unmarried aunts who became professional women at a time when that was unusual. At the age of ten, Georgia decided that she wanted to be an artist. When her family moved to Williamsburg, Virginia, she attended a girls’ boarding school where the art teacher recognized her talent and urged her to go to professional art school after graduation. O’Keeffe’s studies at the Art Institute of Chicago included drawing from plaster casts of idealized human figures made by ancient Greek and Roman artists. She also studied painting at the Art Students League in New York City. Although she excelled in this academic approach, she soon tired of copying traditional art. After working in Chicago for a year as a freelance illustrator, she returned to Virginia and briefly taught art classes at her old high school. At her sister Ida’s suggestion, she enrolled in a drawing class at the University of Virginia. This class, based on the innovative ideas of Arthur Wesley Dow, rekindled her passion for art. Dow stressed self-expression and was inspired by Japanese art principles, such as balancing light and dark, using open space, and respecting nature. Dow taught his students to make harmonious compositions based on the relationship of design elements. O’Keeffe learned about modern art and embraced the idea that pure colors and abstract shapes could express thoughts and feelings. During the next four years, O’Keeffe held teaching jobs in Virginia, South Carolina, and Texas. In South Carolina, she began a series of charcoal drawings called Specials, which she described as “working into my own, unknown—no one to satisfy but myself.” On an impulse, she sent the drawings to her friend Anna Pollitzer in New York City. Pollitzer showed them to a famous photographer named Alfred Stieglitz, who immediately exhibited them at his fashionable gallery! In Education | 1916, O’Keeffe returned to New York City to study with Arthur Wesley Dow at Columbia University’s Teachers College. In New York, she experimented with drawing to music for the first time and she met Alfred Stieglitz. Soon Stieglitz and O’Keeffe began working together, and eight years later they were married. They lived in New York City and spent summers at the Stieglitz family’s country estate in Lake George, New York. By 1929, however, O’Keeffe began to feel cramped by their social lifestyle and decided to spend the summer in Taos, New Mexico. New Mexico reminded her of the wide-open spaces of Wisconsin and Texas and revived her spirits. She returned to New Mexico each summer until Stieglitz’s death in 1946, when she moved there permanently. O’Keeffe continued making paintings and—after her eyesight failed—pottery until her death in 1986. A MODERN WOMAN AND ARTIST Very much a modern woman, Georgia O’Keeffe took full advantage of the opportunities available to women at the beginning of the twentieth century. She traveled on her own and read widely, exchanging ideas with a wide circle of female friends and artists, as well as the group of male artists around her husband, Alfred Stieglitz. Although she was not an activist, she supported women’s struggles for independence at key moments. In 1944 she wrote a letter to Eleanor Roosevelt asking her to support the Equal Rights Amendment: “Equal Rights and Responsibilities is a basic idea . . . I would like each child to feel responsible for the country and that no door for any activity they may choose is closed on account of sex. It seems to me very important to the idea of true democracy—to my country—and to the world eventually—that all men and women stand equal under the sky.” O’Keeffe’s husband, Alfred Stieglitz, was a photographer and also an art dealer who owned a gallery called 291 in New York City. He introduced her to the New York art world, took five hundred photographs of her, ands sponsored twenty solo exhibitions of her work. O’Keeffe and Stieglitz shared similar interests and influenced each other. Stieglitz made Rainbow in 1920, a year after O’Keeffe painted Red and Orange Streak. Can you see the ways in which O’Keeffe influenced Stieglitz? CONNECT AND COMPARE Learn about lightning—what causes it, the different types of lightning, and how different climates and geography affect it. Education | Find out about other American modernists: Arthur Dove, Marsden Hartley, and John Marin. Make a timeline comparing the lives and artworks of Violet Oakley and Georgia O’Keeffe. Research the history of the Equal Rights Amendment. RELATED ART PROJECT Search through memories of storms that you have experienced and pick the most riveting one. Were you at home, at school, or on vacation? In the country, the city, or the suburbs? What part of the country were you in? Was it night or day? How did you feel? Was it a rainstorm, a silent snowstorm, or a roaring hurricane? Make ten small watercolor paintings on index cards, showing the sights and sounds of your storm. Choose the one you like best, or combine elements from several to create a larger composition using oil pastels. This painting is included in Five Women Artists, a set of teaching posters and resource book produced by the Division of Education and made possible by generous grants from Delphi Financial Group and Reliance Standard Life Insurance Company. Education |