Carbon Footprint of War: Environmental Impact & Military Emissions

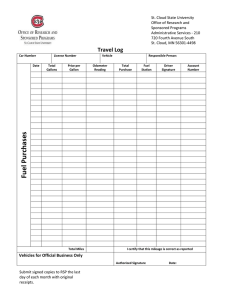

advertisement

JESSE PURCELL Remember the Carbon Footprint of War BY BRUCE E. JOHANSEN 154 A PEOPLE’S CURRICULUM FOR THE EARTH C ompared to the all-too-obvious death and environmental mayhem caused by warfare, the long-range toll of war’s carbon footprint is less visible but hardly harmless. Modern war waged at long distances is hugely carbon dioxide intensive. The U.S. armed forces, which maintain as many as 1,000 bases in other countries, consume about 2 million gallons of oil per day, half of it in jet fuel. Fuel economy has not been a priority in mod- ern fossil-fueled warfare. Humvees average 4 miles per gallon, while an Apache helicopter gets half a mile per gallon. Consumption of fossil fuels has increased over time, with great waste. The Air Force alone uses half the oil consumed by the Department of Defense. For example, it burned through 2.6 billion gallons of fuel during one six-month period in Iraq and Afghanistan in 2006. At that time the armed forces consumed as much fuel per month in limited wars as they did during World War II between 1941 and 1945. Growing Carbon Production At the beginning of World War I in Europe, just over a hundred years ago, the main motive force in battle was the horse and shoe leather, as troops in Europe marched off to battle on foot or horseback. The advent of aerial bombardment and increasing use of tanks caused a dramatic escalation in war’s carbon dioxide production. War is often a powerful technological motor, and carbon-consumption innovator. World War II began with quarter-century-old biplanes and ended with jet-propelled fighters, resulting in a massive increase in fuel consumption. The mechanization of the military provided many more opportunities to ramp up carbon dioxide production during the world wars of the early 20th century. World War II’s Sherman tank, for example, got 0.8 miles per gallon. Seventy-five years later, tank mileage had not improved: the 68-ton Abrams tank got 0.5 miles per gallon. Typical fuel consumption of a fighter jet was 300 to 400 gallons per hour at full thrust, or 100 gallons per hour at cruising speed during hundreds of hours of training and combat missions. Blasting to supersonic speed on its afterburners, an F-15 fighter can burn as much as four gallons of fuel per second. According to Gar Smith in Earth Island Journal, the B-52 Stratocruiser, with eight jet engines, consumes 86 barrels of fuel per hour. Individuals are told to reduce our “carbon footprint,” and we should. But how many years of riding a bike to work would it take for me to offset one F-15 flying for an hour? Assuming that my bike replaces a car that gets 25 miles per gallon, my daily commute of five miles would use a gallon a week. That’s 350 weeks, roughly seven years, to fuel a fighter jet at full thrust for one hour. During the 1950s and 1960s, the U.S. military flew B-52s at all times, on the theory that an airborne fleet would prevent the Soviet Union from obliterating the entire U.S. nuclear-armed armada on the ground. Each of these B-52s burned thousands of gallons of fossil fuel per hour while aloft. That’s 73 bike commuters’ annual fuel savings for every hour a B-52 is in the air. Size, Scope, and Complexity The carbon footprint of war is important and intriguing, but impossible to calculate precisely because of its size, scope, and complexity. The carbon footprint for a bag of potato chips, a carton of milk, or a pair of athletic shoes may be calculated by adding up each unit’s proportion of manufacturing and Individuals are told transportation energy to reduce our “carbon inputs along the entire footprint,” and we life cycle of a product. should. But how Calculating the carbon many years of riding footprint of a single cona bike to work would sumer product is comit take for me to plex, but we can do it. offset one F-15 flying When we become realfor an hour? ly serious about carbon footprints, we will know the amount of greenhouse gases generated by each platoon sent to war, each bomb dropped, each tank deployed. However, today we know the carbon footprint of a bag of potato chips from a Safeway grocery store in California, but war—that elephant in the greenhouse—remains unmeasured. If the Pentagon has ever done such a thing, no one seems to be bragging about it to civilians. The United States launched the Iraq war on the pretext of protecting vital oil supplies, even as it consumed oil at a phenomenal rate. At the start of the Iraq war, in 2003, the United Kingdom Green Party estimated that the United States, Britain, and the minor parties of the “coalition of the willing” were burning the same amount of fuel in the Iraq war (40,000 barrels a day) as all 1.1 billion people living in India. The U.S. Air Force uses 2.6 billion gallons of jet fuel a year, 10 percent of the U.S. domestic market. By the end of 2007, according to a report from Oil Change International, the Iraq war had put THREE: FACING CLIMATE CHAOS 155 at least 141 million metric tons of carbon Today we know the dioxide equivalent carbon footprint of a into the air—as much bag of potato chips from as adding 25 million a Safeway grocery store cars to the roads. The in California, but war— Iraq war added more that elephant in the greenhouse gases to greenhouse—remains the atmosphere than unmeasured. 60 percent of the world’s nations. So how would one begin to sketch the carbon footprint of a war? Here is a preliminary sketch: • First, add all the energy used to produce the weapons, transport, and other provisions consumed in the war. • Add the emissions produced getting soldiers, supplies, and civilian contractors to the theater of war, and home again—in the case of a war pursued thousands of miles from home, often by air transport. Add the cost of running armed personnel carriers, heating and cooling soldiers’ lodgings, and so forth, as well as the greenhouse gases caused by the conduct of combat itself. • Add the carbon and other greenhouse gases added to the atmosphere by fires initiated by bombings and other explosions. In Iraq, pay special attention to intentional sabotage of oil pipelines and suicide bombings, as well as improvised explosive devices. • A dd the carbon cost of tending the wounded. Iraq’s emergency room spanned nearly half the world, from airborne surgery to the Landstuhl Regional Medical Center in Germany and hospitals in the United States. The Urgency of Solutions Peacemakers in our time are often assumed to be naive dreamers. Given the environmental crisis, however, a timely end to war is not naive, but necessary. Armies of the future must study the best ways to solve international conflicts without armed conflict and the monumental pollution that accompanies their death and destruction. The greenhouse gas emissions of war should be regulated on a worldwide basis, and the United States, the world’s premier military power, should take the lead in de-carbonizing international relations. With the carbon footprint of war adding to its cost in blood and treasure, this tally of greenhouse gas emissions should convince us that the Earth can no longer afford fossil-fueled war. q ________________________________________________ Bruce E. Johansen is the Jacob J. Isaacson University Research Professor in the School of Communication and the Native American Studies Program at the University of Nebraska at Omaha. See teaching ideas for this article, page 175. DEFENSE.GOV NEWS PHOTOS 156 A PEOPLE’S CURRICULUM FOR THE EARTH