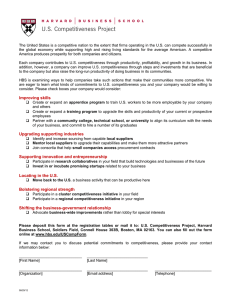

Hot spots - Citigroup

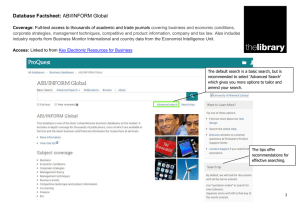

advertisement