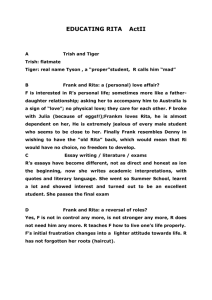

Perspectives on Guided Practice - College of Education

advertisement