Introduction to Mixed Methods in Impact Evaluation

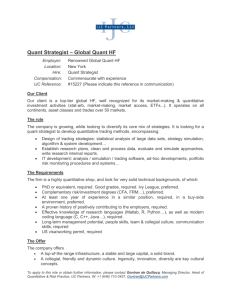

advertisement