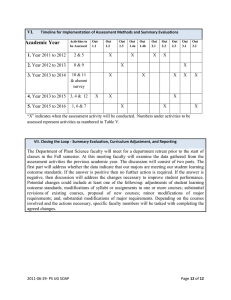

Teacher and Students` Perceptions of a Modified

advertisement

Electronic Journal for Inclusive Education Volume 2 Number 5 Electronic Journal for Inclusive Education Vol. 2, No. 5 (Winter/Spring 2010) Article 6 Winter 2010 Teacher and Students' Perceptions of a Modified Inclusion Classroom Environment Elizabeth Kirby Fullerton Ph.D. e.fullerton@unf.edu Caroline Guardino Ph.D. caroline.guardino@unf.edu Follow this and additional works at: http://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/ejie Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, Curriculum and Social Inquiry Commons, Disability and Equity in Education Commons, Special Education Administration Commons, and the Special Education and Teaching Commons Repository Citation Fullerton, E. K., & Guardino, C. (2010). Teacher and Students' Perceptions of a Modified Inclusion Classroom Environment, Electronic Journal for Inclusive Education, 2 (5). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Journal for Inclusive Education by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact corescholar@www.libraries.wright.edu. Fullerton and Guardino: Teacher and Students' Perceptions of a Modified Inclusion Classro Teacher and Students' Perceptions of a Modified Inclusion Classroom Environment Elizabeth Kirby Fullerton and Caroline Guardino University of North Florida Abstract The purpose of this study was to examine how modifying the inclusion classroom impacts teacher and students’ perceptions of their learning environment. Prior to intervention the teacher was interviewed providing information about her preferred modifications. Following the intervention the teacher completed a rating scale and a post interview. The students completed a classroom environment student survey (CESS), to assess their perceptions of the classroom before, during, and after modifications were made. Twenty fourth grade students, as well as their teacher participated in the study. Implications for practitioners and researchers are discussed. Teacher and Students' Perceptions of a Modified Inclusion Classroom Environment Students and teachers are the experts on their classroom environment. When changes are made to the classroom (i.e. group and individual learning spaces), understanding how the experts feel about the changes may influence the overall learning. The purpose of this study was to examine the impact classroom modifications had on teacher and student perceptions. Additionally, the teacher’s perceptions of the classroom modifications were examined to determine the acceptability of the intervention. The teacher’s use of her classroom environment as a behavior management technique can set the stage for productive learning (Gazin, 1999). Her perception of that space is an indication of her use of classroom arrangement as a behavior management tool. The students’ perception of the classroom Published by CORE Scholar, 2010 1 Electronic Journal for Inclusive Education, Vol. 2, No. 5 [2010], Art. 6 environment provides the teacher with (1) an idea of whether or not the classroom engages them in learning (Geiger, 2000) and (2) a measure of whether or not she is using the environment effectively. The classroom environment (i.e. arrangement of furniture, access to materials) is the first step in creating a well-managed classroom (Kerr & Nelson, 2002). The physical environment refers to the use of space, arrangement of furniture to promote individual and group learning, as well as availability of resources and material for students (Dodge & Colker, 1996). Although a quick Internet search can provide teachers with a myriad of tips about the environment, a dearth of research has been done on the impact classroom modifications have on the way teachers and students view their learning environment. After modifications are made, if the teacher sees improvement in student behavior she is more likely to sustain the modifications that are in place, implement additional modifications, and use them in future classrooms (Diamantes, 2002; Guardino, 2008). A limited number of studies have shown that modifications to the classroom environment positively impact the way in which teachers and students view their classroom. For example, HadiTabassum (1999) evaluated how changes in the classroom environment impacted academic learning for 25 students in the 8th grade considered at-risk for academic failure due to limited English, low-test scores and socioeconomic status. The study examined if changes to the classroom environment (i.e. more cooperative group work) altered the students’ attitude toward the class. The findings indicate that when changes were put in place not only did the students report a more positive attitude towards the class, but also academic learning improved. Diamantes (2002) studied students’ perceptions about the classroom environment to guide teachers in making environmental improvements. Specifically, 1216 sixth to eighth grade science students were surveyed to differentiate their perception of an ideal environment compared to their preferred environment. The student responses were used to guide six of twelve teachers to make changes to the classrooms (six of the twelve were a control group). As with the previous study students http://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/ejie/vol2/iss5/6 2 Fullerton and Guardino: Teacher and Students' Perceptions of a Modified Inclusion Classro were considered at-risk based on low-test scores, limited English proficiency, and socioeconomic status. Diamantes stated that the students provided valid information about their preferred and ideal environtment which helped the teachers make changes to the science classrooms. Student grouping was one of the four changes made which teachers perceived as improving the satisfaction of the environment. The researcher stresses that teacher and student satisfaction of their classroom can lead to improved learning. Johnson (2006) examined the perceptions of 214 fifth and sixth grade students on their learning preferences as well as classroom-learning environment. The results indicate that students preferred group over individual learning which was impacted by their perception of the physical arrangement of the classroom. Rivera and Waxman (2007) examined 223 fourth and fifth grade students’ perceptions of their classroom behavior and learning environment. As with the previous studies the students were considered at-risk due to limited English proficiency as well as socioeconomic status. The study compared the differences between those students who were faring better academically to those who were struggling in school. The findings indicate that those who positively perceived their learning environment were performing better academically than those who did not. The studies indicate that teachers and students have insight into their classroom environment. Their views impact, to some extent, their academic learning. Furthermore, teachers can use this information to make modifications to the environment that will lead to more productive learning. Despite these findings, previous research has not examined the teacher’s and students’ perceptions of their classroom before, during and after modifications are put in place. Expanding this line of research may help refine which modifications have the biggest impact on students’ academic and behavioral performance. In addition, continued research will enable teachers to effectively use classroom modifications as a behavior management tool. Published by CORE Scholar, 2010 3 Electronic Journal for Inclusive Education, Vol. 2, No. 5 [2010], Art. 6 This study specifically addresses the following questions: 1) What are the teacher’s perceptions of the modifications made to her classroom environment? (2) What are the teacher’s perceptions of the effectiveness of the modifications on whole class academic engagement and disruptive behavior? (3) How do the students’ perceptions of their classroom environment change when their classroom is modified? Methods Participants and Setting The participants were 20 fourth grade students and one teacher in an inclusion classroom located in an urban area of the southeastern United States. The students were considered at-risk for academic failure due to low standardized test scores and socio-economic status. The classroom population reflects that of the school where at least 90% of the students were eligible for free or reduced lunch. In addition, the school has failed the mandatory statewide testing annually since 2003. Of the 20 students, one qualified for special education services. In addition, the teacher and principal reported the students had a higher than expected level of suspensions (in school and out of school) due to disruptive behavior. This study was conducted during the teacher’s first year of teaching and she requested additional help to manage her students’ behavior. Measures The target behaviors of this study were teacher and student perceptions of their inclusion classroom environment. The teacher’s perception of her classroom environment was collected through pre- and post- interviews, as well as completion of the Modification Rating Scale-Teacher (MRS-T). The students’ perceptions of their classroom environment was collected through a survey. Pre-intervention interview. The pre-intervention interview consisted of five questions on the teacher’s perception of where, when, and what types of disruptive behavior occurred in her 1[1] http://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/ejie/vol2/iss5/6 4 Fullerton and Guardino: Teacher and Students' Perceptions of a Modified Inclusion Classro classroom. The questions also required the teacher to describe how she used various areas in the classroom throughout the day. Lastly, the teacher identified what she felt was the best academic learning time for the researchers to observe the classroom and collect data. Modification Rating Scale-Teacher (MRS-T). The MRS-T was created by the researchers to reflect both categorization and ranking of the modifications made to the classroom. Classroom modifications used in the study were grouped into categories. For example, hanging motivational posters and pasting rules would fall under the category of “visual-auditory stimuli”. Whereas, adding shelves near teacher’s desk and organizing the supply cabinets would be categorized as “organization”. Dependent on the number of items in each category, each modification is ranked separately as having the “greatest” to “least” effectiveness on levels of academic engagement and disruptive behavior. At the bottom of the scale each of the categories are listed and the teacher assigns an overall ranking. The teacher’s ranking allowed the researchers to determine her perceptions of what modifications she felt had the greatest impact on academic engagement and disruptive behavior. The modifications teachers choose for their classrooms are based on the needs of their specific class as well as the teacher’s individual preferences, the MRS-T categories and subsequent modifications vary class to class. Post-intervention interview. The post-intervention interview consisted of opened-ended questions designed to encourage the teacher to reflect on her experience while participating in the classroom modification study. The interview measured the acceptability of the intervention by the teacher. The interviewer, one of the researchers, asked the teacher to discuss : 1) what she liked most, (2) what she would do differently, (3) would she continue to use the modifications, (3) did her students benefit, (4) would she recommend the intervention to other teachers, and (5) did the modifications change her behavior in their classroom? Student perception survey. Student perceptions of their classroom environment were measured by a 5- question survey. The students answered questions by circling a smiley or sad face. The Published by CORE Scholar, 2010 5 Electronic Journal for Inclusive Education, Vol. 2, No. 5 [2010], Art. 6 researchers read the instructions to the students as, “Let’s start by discussing what the faces mean. A smiley face means what? A sad face means what? Great! Now I will read a question and you circle either the smiley face or the sad face.” (see Figure 1). A smiley face signified that the student was content with the specified aspect of their classroom (i.e. group area, desk space). A sad face indicated that the student was unsatisfied with the specified aspect of their classroom. The researchers administered the survey three times: at the start of pre-intervention data collection, and then approximately two-days, and four-weeks after the intervention. Procedures Pre-intervention phase. A 30-minute pre-intervention interview was conducted. The teacher discussed areas where disruptive behavior was a concern, times throughout the day where disruptive behavior was prevalent, types of disruptive behaviors, ways she utilized various areas in the classroom, and optimal times for observing disruptive behaviors. After the interview, the researchers observed whole class and teacher behaviors over a 2-week period. Observations were 15-minutes in length. The students were administered the student perception survey. Intervention phase. After pre-intervention behaviors were documented, the researchers met again with the teacher to decide which classroom modifications she preferred. The teacher expressed interest in reducing the clutter, reorganizing her desk area, and adding a group space. She was also concerned with the classroom library that had several containers of books consuming the majority of the carpet space. Over the course of one Friday afternoon and Saturday morning, while no students were present, the teacher and researchers completed the classroom modifications. (See the MRS-T for a list of the classroom modifications.) When the students returned on Monday, they completed the student perception survey for the second time. Post-intervention phase. Five weeks after completion of the intervention, the researchers met with the teacher to complete the MRS-T and the post-intervention interview. Completion of both data http://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/ejie/vol2/iss5/6 6 Fullerton and Guardino: Teacher and Students' Perceptions of a Modified Inclusion Classro collection materials took approximately 45-minutes. The students completed the student perception survey for the third and last time. Results Teacher’s Perceptions Pre-intervention interview. The teacher reported that disruptive behaviors typically occurred when students were placed in dyads or worked in small groups. She stated that morning and after-lunch work periods were typically the time of day when the students were most disruptive. Disruptive behavior ranged from speaking without permission, getting out of seat, making unwanted physical contact, or non-compliance to teacher direction. The teacher explained to the researchers that she had the student desks arranged in dyads and used this design for both group and individual work periods. During periods of group work, the students had to rearrange their desks into larger quadrants, which always resulted in high levels of disruption. She reported that a reading coach used a small table situated in the back corner of the classroom for individual testing. Although there was a computer table with two computers, she stated the area was not used because the computers were not working. At the end of the meeting the researchers and teachers determined the best time to observe the classroom was during reader’s workshop at 9am, Monday through Thursday. Modification Rating Scale-Teacher. A total of 16 modifications were made to the classroom. Of the 16 modifications, four categories were determined: visual-auditory stimuli, organization, personal and group workspace, and clear pathways. See Table 2 for a summary of the teachers’ perceptions of which modifications had the greatest to least effect on academic engagement and disruptive behaviors. Overall, the teacher believed the “personal and group work space” modifications had the greatest impact on reducing the levels of disruptive behavior in the classroom. Modifications in this category included providing individual work carrels, adding chair bags (bags that hang from the back of the student’s chair) for personal supplies, and creating distinct “group” workspace (see Figure 3). She Published by CORE Scholar, 2010 7 Electronic Journal for Inclusive Education, Vol. 2, No. 5 [2010], Art. 6 ranked the category “clear pathways” as having the least effect on disruptive behavior. Specifically, the teacher perceived that rearranging the teacher’s and students’ desks had little impact on the level of disruptive behavior in the classroom. The teacher ranked the category “personal and group work space” as having the greatest impact on levels of academic engagement. She continued to rank the remaining three categories in the following order from next greatest to least effective: cleared pathways, organization, and visual-auditory stimuli. Post-intervention interview. After completing the MRS-T, the teacher answered all 10 openended questions in the post-intervention interview. The teacher responded that she liked the new arrangement of the classroom furniture as it allowed the students to see the board simultaneously. This report is consistent with her rankings of effectiveness of modifications on academic engagement. If she were able to do this intervention again, she reported that she would have requested smaller desks to save on personal space and increase group space. The teacher stated that she will use the modifications she learned from this study to design her classroom in the beginning of the school year next fall. She believed the students definitely benefitted from the classroom modifications, especially the personal chair bags and reorganization of classroom storage area. Not only would she recommend this intervention to other teachers, but also she reported that other teachers used her re-designed classroom as a model for rearranging their classroom furniture. Students’ Perceptions Student perception survey. Overall classroom mean percentages were calculated across the three phases: pre-intervention, intervention, and post-intervention (see Table 1). The percentages of students who circled a happy face for each of the 5-items across all three phases are reported in figure 2. A summary of the figure shows that from the pre-intervention to post-intervention phase the students felt increasingly happier about their classroom environment, from 58% to 79% respectively. http://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/ejie/vol2/iss5/6 8 Fullerton and Guardino: Teacher and Students' Perceptions of a Modified Inclusion Classro This also remains true for their ability to “walk around my classroom without running into kids or things (chairs, books, shelves)”, 50% to 71% respectively. There were two areas where students where more “content” during the intervention phase than during the post-intervention phase. Sixty-seven percent of the students felt happy about their group space during the intervention phase, whereas only 36% continued to feel happy during the postintervention phase. This is also true of “knowing where everything belongs in my classroom”. Eighty percent of the students circled the happy face during the intervention phase, whereas only 71% circled the happy face during the intervention phase. Although both of these “happy” percentages declined during the post-intervention phase, both percentages are an average of 12% higher than during the preintervention phase. The students’ perception of their ability to work quietly at their desk declined from preintervention in both the intervention and post-intervention phases. During pre-intervention 75% of the student felt “happy” about working quietly at their desk, while intervention and post-intervention percentages were 40% and 57% respectively. Possible reasons for this decline will be discussed in the following section. Limitations Although the results of this study are positive, the limitations should be recognized and reviewed with caution. The sample size was small with one class and one teacher participating in the study. A larger sample of students and teachers would improve the generalization of the results. Student absenteeism, tardiness, suspension, removal for testing or tutoring, altered the number of respondents during each phase. The results from the student survey are limited because item response means were averaged across the class, not allowing for individual student perception changes. In future studies, assigning students a number would allow individual and groups of student scores to be compared across phases. Item number five of the student perception survey should be changed from “our group space Published by CORE Scholar, 2010 9 Electronic Journal for Inclusive Education, Vol. 2, No. 5 [2010], Art. 6 makes me feel” to “I can do work in our group space”. A semantic change will provide important information on whether or not students can stay on-task in-group areas. Finally, once the modifications were in place the teacher had difficulty sustaining the changes. For example, the students requested the carrels during individual work time, but the teacher did not use them consistently. Conclusion The purpose of this study was to examine the effectiveness of classroom modifications on teacher and student perceptions of their fourth grade inclusion classroom. The findings indicate that the teacher positively perceived the modifications and believed they helped improve student behaviors. The students perceptions also changed as overall they were more content with the new arrangement. Teachers would benefit from effectively using their classroom environment to positively manage student behavior. The results of this study emphasize that modifying the classroom has an impact on the teacher’s perception of the environment. More research is warranted to determine if including teacher training on how to utilize the modifications increases the effectiveness of the intervention. Teachers need to be a partner in the change and must be able to sustain the changes until desired results (increase in on-task behavior and decrease in disruptive behavior) are attained (Diamantes, 2002). In addition, the students’ perceptions of the classroom are good indicators of what might need to be changed. Including their perceptions in the modifications may increase engagement in the learning. The students’ perceptions of their environment are an important dimension of the current study and future research. Students’ positive perception of the environment decreased in two areas during the post-intervention phase (group space and everything belongs). This could be related to two factors: (1) the number of students increased thus making the group work more crowded, and (2) the teacher did not specifically model how to use the chair bags and study carrels. This may also explain the drop in the students’ positive perception of working quietly at their desk. At the start of the intervention phase http://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/ejie/vol2/iss5/6 10 Fullerton and Guardino: Teacher and Students' Perceptions of a Modified Inclusion Classro each student was given a carrel to personalize. As the intervention continued the teacher stopped using the carrels even when a student requested it. In the future, the teacher suggested that the researchers add a component to the intervention that would teach her how to utilize some of the modifications to better maximize their usefulness. For example, while the individual desk carrels were helpful, it was difficult for the teacher to determine how and when to use them. With additional support from the researchers, the teacher could be trained to use the carrels effectively. In conclusion, the teacher reported that the modifications changed her behavior, as she was able to see to that the students wanted to work once they were given the chair bags and carrels. Overall, the modifications had a positive impact on the learning environment. The children had clearly defined group spaces that they used effectively. Although there was an increase in the number of students, the pathways remained clear (could walk without running into things, move between individual and group areas without contacting another student). This study has shown that when classrooms undergo small changes, meaningful positive perceptions by students and teachers are gained. References Diamantes, T. Improving instruction in multicultural classes by using classroom-learning environments. (2002). Journal of Instructional Psychology v. 29 no. 4 277-82. Dodge, D. T. & Colker, L. J. (1996). The creative curriculum (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Teaching Strategies. Gazin, A. (1999). Keeping them on the edge of their seats. Instructor , 109 (1), 28-30. Geiger, B. (2000). Discipline in K through 8th grade classrooms. Education (Chula Vista, Calif.), 121(2), 383-393. Published by CORE Scholar, 2010 11 Electronic Journal for Inclusive Education, Vol. 2, No. 5 [2010], Art. 6 Guardino, C. (2008). Modifying the classroom environment to reduce disruptive behavior and increase academic engagement in classrooms with students who have a hearing loss. (Doctoral Dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest. (AAT 3304010) Hadi-Tabassum, S. (1999). Assessing students' attitudes & achievements in a multicultural & multilingual science classroom. Multicultural Education, 7 (2), 15-20. Johnson, L. (2006) Elementary School Students’ Learning Preferences and the Classroom Learning Environment: Implications for Education Practice and Policy. The Journal of Negro Education, 75 (3), 506-518. Kerry, M., & Nelson, C. (2002). Strategies for addressing behavior problems in the classroom. (4ed.) New Jersey: Merrill Prentice Hall. Footnotes 1[1] Because the teacher in this study is female, the authors refer to the teacher as “she”. However, any teacher could complete the rating scales. http://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/ejie/vol2/iss5/6 12 Fullerton and Guardino: Teacher and Students' Perceptions of a Modified Inclusion Classro Table 1 Pre-intervention, Intervention, & Post-intervention Percentages of Student Perception Survey Pre-Intervention N=12 Intervention N=15 Perception Question Happy Unhappy Happy Classroom feel 58 42 60 Quiet work at desk 75 25 Group space feel 25 Items belongs Walk Unobstructed Published by CORE Scholar, 2010 Unhappy Post-intervention N=14 Happy Unhappy 40 79 21 40 60 57 43 75 67 33 36 64 58 42 80 20 71 29 50 50 60 40 71 29 13 Electronic Journal for Inclusive Education, Vol. 2, No. 5 [2010], Art. 6 Table 2 Results of the Modification Rating Scale-Teacher (MRS-T) ranked from greatest (1) to least effectiveness. Disruptive Academic Modifications Behavior Engagement Visual-Auditory Stimuli Straightened materials in several areas of the classroom 1 4 Straightened and reduced books in library area 4 2 Hung posters of role models & positive sayings 3 3 Added plants for sound buffer and add hominess to class 6 6 Rearranged computer area to minimize visual distractions 5 5 Pasted rules inside carrels 2 1 Add shelves to left of teacher’s desk 3 3 Organized all cabinets to reflect current curriculum use 2 2 Two squat shelves added under ½ moon main table 1 1 Individual Carrels 1 1 Added chair bags for personal supplies and “sponge” activities 3 2 Added table for a third “group” work space 2 3 Separated large area rug for 2 distinct “group” work areas 4 4 Moved reading area to center: more accessible & obvious reward 2 3 Rearranged area access to teacher’s desk 3 4 Rearranged desks 4 1 Moved ½ moon to front of classroom for accessibility 1 2 3 4 Organization 2 3 Privacy-Independent Work Space 1 1 Clear pathways 4 2 Organization Personal & Group Work Space Clear pathways Reduce Visual Stimuli http://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/ejie/vol2/iss5/6 Category Ranking 14 Fullerton and Guardino: Teacher and Students' Perceptions of a Modified Inclusion Classro Figure 1. Survey used to determine students’ perception of their classroom environment during preintervention, intervention, and post-intervention phases. 1) My classroom makes me feel: 2) I can do quiet work at my desk: 3) Our group space makes me feel: 4) I know where everything belongs in my classroom. 5) I can walk around my classroom without running into kids or things (chairs, books, shelves). Published by CORE Scholar, 2010 15 Electronic Journal for Inclusive Education, Vol. 2, No. 5 [2010], Art. 6 Figure 2. Percentage of students who circled “happy” during pre-intervention, intervention, and post-intervention phases. Pre-Intervention (N=12) Intervention (N=15) Post-Intervention (N=14) Figure 3. Illustration of individual work space with carrels and group work space. http://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/ejie/vol2/iss5/6 16