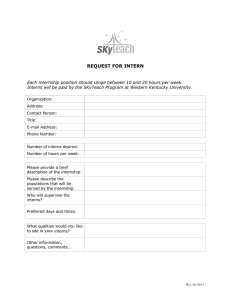

Supported internships

advertisement