NOTE SHEETS - California State University, Los Angeles

advertisement

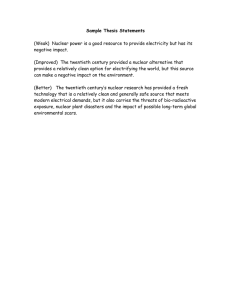

History 388 WRITING “NOTE SHEETS” Chris Endy Note sheets may be typed or hand-written and are due at the start of class. I will evaluate them based on content rather than on style or spelling (with the exception of the citation). You should always come to class with TWO COPIES of your note sheet. One is for me and the other is for you to use during class. Each note sheet should have the following seven elements: 1. The Citation: Create a heading that provides a full citation for the article or book in question. It’s a good habit to have this information in your notes so that you can cite the work in later papers. Failure to use the Chicago Manual of Style documentary-note style will result in a halfpoint deduction from the note sheet grade. See below for examples of this format. For more details on the Chicago documentary-note format, see http://www.calstatela.edu/library/styleman.htm. Article: Ronald W. Lopez, “The El Monte Berry Strike of 1933,” Aztlan 1 (Spring 1970): 101-14. Book: George J. Sanchez, Becoming Mexican American: Ethnicity, Culture and Identity in Chicano Los Angeles, 1900-1945 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993). Chapter in an Edited Book: Susan Porter Benson, “‘The Customers Ain’t God’: The Work Culture of Department-Store Saleswomen, 1890-1940,” in Working-Class America: Essays on Labor, Community, and American Society, eds. Michael H. Frisch and Daniel J. Walkowitz (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1983), 185-211. 2. The Thesis: Write the author’s main thesis in your own words, in one or two sentences. Remember, a thesis is the author’s argument or conclusion, not simply the author’s topic or question. 3. The Primary Sources: Briefly describe the main categories of primary sources used by the author. For instance, does the author look at only public speeches or also at declassified government documents? Public opinion polls or private diaries? Census data or oral histories? You should not copy specific names from the notes. Focus instead on the general nature of the author’s primary sources. Also, do not list the author’s secondary-source citations. 4. The Sections and Subtheses: Divide the body of the article into sections. Usually I will give instructions for each note sheet on how to do this. Then identify each section’s main argument (a subthesis). Write each subthesis in your own words, in one or two sentences. Also provide the page numbers for where the section begins and ends. Failure to provide page numbers will result in a half-point deduction. A subthesis should always be an argument (not just a topic), and it should help develop or support the author’s overall thesis. When appropriate, write down the main idea of the author’s epilogue. An epilogue is a closing idea or flourish that extends the main thesis to a time or place different than those discussed in the body of the article or book. Imagine a journal article with three subsections. First you would read the introduction and conclusion of the article to identify the thesis and any possible epilogue. You do not include the introduction or conclusion in the sections/subtheses part of the note sheet. The sections/subthesis part would look something like this: Subthesis 1: You write the main argument of the first section in your own words in 1-2 sentences. You also provide that section’s starting and ending pages numbers in parenthesis Subthesis 2: Repeat for the second section Subthesis 3: Repeat for third section. Epilogue in the Conclusion: Write the epilogue flourish idea in 1-2 sentences, along with the page #s. If the conclusion has no epilogue idea, simply skip this step. 5. Historiographic Traits: What historiographic traits or labels apply to this author? Use your class notes and the glossary for help. Be sure to explain where or how you see this trait in the author’s approach. Do not simply list a trait without explanation for why it applies. 6. Strengths: (see “weaknesses or limits” below) 7. Weaknesses or Limits: Parts 6 and 7 are where you bring your own critical mind to the reading. To help brainstorm ideas, consult your class notes and my online tips for reading. While it’s ok to focus on side items or smaller points in each article, be sure to comment on the most important issue: how well does the author prove his or her main points? For each note sheet, you should have at least two thoughtful comments to say on “Strengths” and at least another two for “Weaknesses or Limits.” You can use bullet or outline form here, but be sure to write in full sentences. SAMPLE NOTE SHEET Homer J. Simpson, “The Secret History of Nuclear Power in the United States,” Springfield Journal of History 23 (January 2013): 12-35. Thesis: Nuclear power emerged in the 1950s and 1960s not because it was more efficient but because of a sinister propaganda campaign. As a result, Americans today pay environmental and financial costs. -Although Simpson is largely critical of the nuclear power industry, he recognizes the industry’s ability to diversify our overall energy grid. This brings some balance to a controversial issue. Weaknesses or Limits: -He lacks clear evidence on the role of vampires. His footnotes here (pages 14-18) refer only to TV shows. Are these reliable sources? Primary Sources: Archives of energy companies (especially Springfield Power), interviews with plant owners and workers; documents from state and federal government’s energy agencies. -Simpson says little about whether workers in nuclear power plants believed the ideology that elites like Montgomery Burns promoted. More research on the bottom-up level could determine just how successful this elite propaganda campaign was. He could have used labor union newsletters or oral histories with workers to research this. Subtheses: Subthesis 1: Contrary to conventional histories that describe public utilities as the driving force behind nuclear power, Simpson argues that the real push came from Montgomery Burns, who was the leader of a secretive vampire society (pp. 12-22). -Could it be that a different group of elites controlled children’s television? Simpson assumes that anyone who says anything favorable about nuclear power is somehow tied to the Burns/vampire conspiracy. Subthesis 2: Burns’s secret society created a propaganda campaign to spread the ideology of nuclear power (pp. 22-28). Subthesis 3: Burn’s vampire conspiracy eventually spread into other areas of U.S. society, especially children’s television shows (pp. 28-35). Epilogue: Simpson suggests that what was true for nuclear power in the 1950s and 1960s is also true for solar energy today. (p. 35). Traits: -Top-down approach, since almost all his sources came from business executives. -Political history from a leftist perspective, since Simpson is concerned with the political process behind nuclear power, and he also seems very critical of big business. -Also some cultural approach, since Simpson uses the technique of thick description to uncover the hidden emotional meanings embedded in nuclear industry propaganda publications. Strengths: -Wide variety of elite sources helps Simpson see the topic from a behindthe-scenes insider perspective. He did more than simply look at the nuclear power industry’s public rhetoric. This helps prove his thesis on the presence of a propaganda campaign promoting nuclear power. FEEDBACK CODE FOR NOTE SHEETS •Feedback code for the most common shortcoming when students describe an author’s strengths: When I write _____________________ on your note sheet, it means, “You have identified a potentially good idea for praising the author, but you need to actually explain how this strong feature specifically helped make the author’s thesis or subthesis more persuasive.” Example of a flawed strength comment: -“Simpson did a good job with a lot of sources.” •Feedback code for the most common shortcoming when students describe an author’s weaknesses or limits: When I write _____________________ on your note sheet, it means, “You have done a good job identifying a missing perspective, topic, or type of primary source in the author’s scholarship. However, you should finish the critique by taking the important extra step of explaining how more attention to that missing perspective, topic, or source might have improved or altered the author’s thesis/subthesis.” Example of a flawed weakness or limit comment -“Simpson should have included bottom-up sources.”