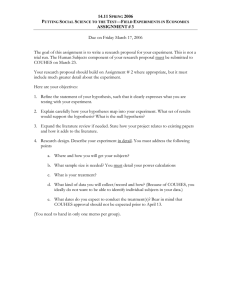

Influence of Prior Knowledge on Concept Acquisition

advertisement