(MB-EAT) for Binge Eating - Indiana State University

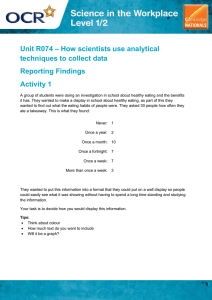

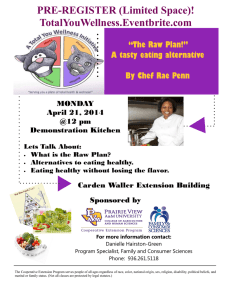

advertisement