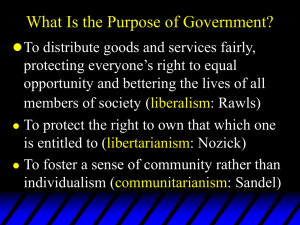

the shape of lockean rights

advertisement