LED Airfield Lighting System Operation and Maintenance | Blurbs

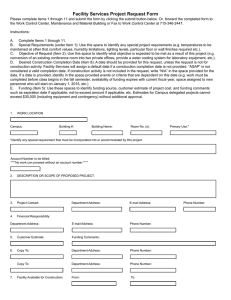

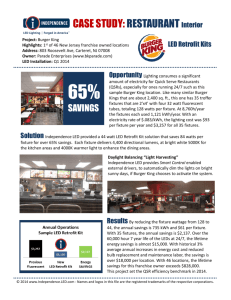

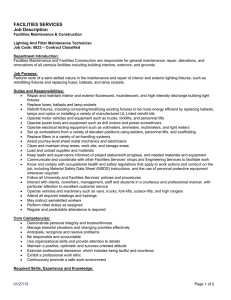

advertisement