The mental health of serving and ex

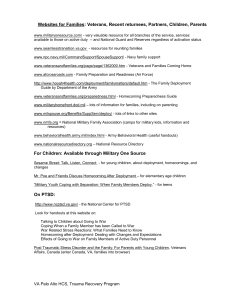

advertisement