ZOOMING PAST POINT AND SHOOT!

advertisement

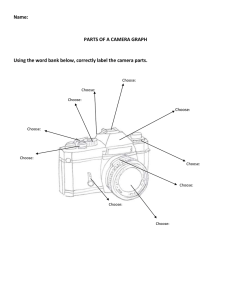

46 ZOOMING PAST POINT AND SHOOT! M AT C H B O X ™ I S A T R A D E M A R K O F M AT T E L , I N C . GUIDE TO DIGITAL PHOTOGRAPHY, PART I REVIEWS AND RESOURCES LENS There are a number of informative web sites, books, and magazines that can help you make a good decision when you are ready to buy. Each is updated frequently, which is critical with the pace of change in the digital camera industry. APERTURE. The circular area behind the lens that opens to allow light in and expose the film or digital CCD. Most cameras can vary the aperture’s diameter to control the amount of light reaching the exposure plane. ON-LINE DEPTH OF FIELD. The difference between the nearest and furthest in-focus objects. The smaller the aperture, the larger the fstop value, and the more background will be in focus. • WWW.DPREVIEW.COM, it’s by far the most informative and comprehensive site on digital cameras, with in-depth reviews of most camera models by a very experienced photographer. Bookmark this one site if no where else. • WWW.AMAZON.COM, can’t beat the selection. • WWW.MYSIMON.COM, to search for the best available price; read the small print for shipping, make sure the camera isn’t “gray market” from offshore—it voids the warranty. NEWS STAND • DIGITAL PHOTO, also on the web at www.pcphotomag.com FSTOP. A measurement of the diameter of the aperture’s opening during exposure. The lower the fstop, the larger the aperture will open and the more light will be sent to the sensor. For example, if you set the aperture to f/2.8, it is larger than f/8. FILM SPEED/ISO. The sensitivity of a given film to light, indicated by the ISO [International Standards Organization] number. The higher the number, the more sensitive or faster the film becomes. Some digital cameras have an ISO setting that emulates film ISO by varying the CCD’s light sensitivity. The digital image can be made to appear like a print from film with the corresponding ISO level. • DIGITAL PHOTOGRAPHY MADE EASY, one of several outstanding publications from the U.K. You can find it and others at larger bookstores or news stands. FOCAL LENGTH. The distance between the film and the optical center of the lens when the lens’ focus is set to infinity. BOOK STORE OPTICAL VS. DIGITAL ZOOM. Optical zoom cameras rearrange and move internal lenses to achieve magnification. Digital zoom enlarges the image via pixel interpolation, like Photoshop, resulting in a lower-quality image. Because digital zoom doesn’t generate any new image data, you don’t see extra detail when compared to optical zoom. There are hundreds of books on photography and easily dozens on digital photography. Two that we’ve found useful are on filters and their use. • HOW TO DO EVERYTHING WITH YOUR DIGITAL CAMERA, by Dave Johnson • THE PHOTOGRAPHER’S GUIDE TO FILTERS, by Lee Frost • USING FILTERS, published by Kodak Books INFINITY. The farthest-away position of focus. OVER- AND UNDEREXPOSURE. Too much or too little light reaches the exposure plane. Overexposure results in a light image with lost highlight detail, and underexposure results in a dark or muddy-looking image with lost shadow detail. SHUTTER SPEED. The length of time the camera’s aperture remains open during the exposure of the photograph. The slower the shutter speed, the longer the exposure time. The shutter speed and the aperture together control the total amount of light reaching the sensor. GLOSSARY AND RESOURCES LIGHTING ACETATE. Clear plastic-like sheet often color tinted and fitted over studio lights. AMBIENT LIGHT. Natural, outdoor light. SOFT BOX. Popular lighting accessory that produces extremely soft light. Various sizes and shapes are available; the larger they are, the more diffuse the light. SPOT. A directional light source. BARN DOORS. Set of four flaps that fit over the front of a studio light to control the direction of the light. SWIMMING POOL. Large soft box giving soft lighting. BOOM. Long arm fitted with a counterweight which allows studio lights or reflectors to be positioned above the subject UMBRELLA. Lighting accessory used to bounce a light source from and onto a subject. They come in a range of colors. The larger the umbrella, the softer the light. CONTINUOUS LIGHTING. Sources that provide steady illumination, in contrast to flash which fires briefly. DIFFUSER. Any kind of accessory which softens the output from a light source. EFFECTS LIGHT. Studio light used to illuminate a specific part of the subject. FILL LIGHT. Studio light for reducing shadows. FLASH HEAD. Studio lighting unit which emits a quick and powerful burst of light. INCIDENT READING. Exposure reading of the light falling onto the subject. KELVIN. Scale used for measuring the color of light. Daylight and electronic flash is balanced to 5500K. DIGITAL FILE 8-BIT VS. 16-BIT. The amount of data (2 vs. 2 ) that can be used to describe the grayscale tone gradation for red, green or blue, for each pixel. An 8-bit image has 256 levels of tone description of each color for every pixel in the image. 8 16 CCD. [Charge Coupled Device] The light-sensitive instrument that records the image. Made up of thousands of pixel-sized sensors, each of which typically read only red, green or blue. The camera’s “megabits” represent an approximate rounding of the size of the CCD array, which is determined by multiplying its horizontal pixel-sensors by its vertical ones. The camera we used is a 4-megabit camera, since its CCD measures 1,722 x 2,274 pixels, which totals roughly 4 million. KEY LIGHT. The main lighting source. PIXEL. [Picture Element] The building blocks of a digital photo, and single unit of light capture. LIGHT METER. A light-sensitive tool built into most digital cameras that determines the light level(s) of the image. A camera uses these readings to determine the exposure length. RAW FORMAT. The uncompressed data as it comes from the CCD. This may contain additional detail that can improve image quality when compared to saving in the JPEG format. MULTIPLE FLASH. Firing a flash head several times to give the amount of light required. RESOLUTION. The density of pixels per measurement unit, expressed as a number of horizontal pixels by a number of vertical pixels. “300 DPI” scans measure 300 horizontal x 300 vertical pixels for a total of 90,000 pixels per square inch. REFLECTOR. Metal shade around a light source to control and direct it, or a white or silvered surface used to redirect light. RINGFLASH. Circular flash tube which fits around the lens and produces a characteristic shadowless lighting. SCRIM. Any kind of material placed in front of a light to reduce its intensity. SNOOT. Black cone which tapers to concentrate the light into a circular beam. Guide To Digital Photography © 2004 All rights reserved. 3 FSTOP FSTOP 2.5 GREATER EMPHASIS ON THE POINT OF FOCUS. We captured this image with the fstop set to 2.5. The low fstop results in lessened depth of field and heightens emphasis on the point of focus (the rear tire). We relied on the camera to determine the right exposure time based on the manual fstop setting. This shot required an exposure of 1/10 second, much less time (and light) required to capture an image with a lower fstop. This is specially relevant if you are shooting without a tripod. The longer the exposure, the steadier the hand must be! FSTOP/APERTURE (MANUAL): 2.5 SHUTTER SPEED (AUTO): 1 /10 SECOND WHAT IS THE FSTOP? The fstop setting controls the diameter of the aperture, the temporary opening that allows light to enter and expose the image media as you take a picture. WHAT DOES IT MEASURE? The higher the fstop, the smaller the diameter of the aperture during exposure. WHAT IS THE IMPACT? A lower fstop results in a shorter depth of field, which is the area of foreground and background relative to the focal point that remains in focus. Notice that the El Camino behind the Corvette, as well as the Corvette’s shadow, are out of focus at this camera’s lowest supported fstop setting (2.5), whereas they are crisper at its highest fstop setting (8.0). WHAT ABOUT EXPOSURE? FSTOP 8.0 FSTOP/APERTURE (MANUAL): 8.0 SHUTTER SPEED (AUTO): 1 SECOND 4 Guide To Digital Photography © 2004 All rights reserved. GREATER DEPTH OF FIELD. We captured this image with the fstop set to 8.0, the camera's maximum. Notice the increased detail in both the foreground and the background, as the higher fstop results in a deeper depth of field. The resulting image benefits from increased clarity (more seems in focus), while reducing the emphasis and impact of the point of focus. Note that the exposure time required, which the camera set based on our fstop setting, increased to one full second, which requires a tripod to maintain a steady camera through the exposure and avoid a blurry photograph. To compensate for the decrease in volume of light, exposure time (shutter speed) must increase as the fstop increases. During the capture of these images, we used the camera’s built-in light meter to keep the light an approximate constant. The exposure time had to be 10 times longer to maintain the same brightness at an fstop of 8.0 vs. 2.5. Note that all of these exposures were made at a very low film speed (ISO setting of 50), which resulted in a long exposure requirement across the board. Also note that it would take an extraordinarily-steady hand to shoot these images without a tripod. The exposure times are just too long, and even a little bit of movement will result in a blurry shot. ISO VALUE WHAT DOES ISO MEASURE? ISO 50 ISO, which stands for International Standards Organization, is a measure of the relative light sensitivity of photographic film. The higher the number, the more sensitive or faster the film becomes, creating a correctly-exposed image in less time. Higher-speed film is typically used to capture sports and other action shots. DOES IT APPLY TO DIGITAL? As with other mid-range to high-end digital cameras, the Canon Powershot G2 we used has an ISO setting that controls the sensitivity of the light sensor (referred to as the charge-coupled device or CCD). Use this to impose a specific exposure or look-and-feel to your image. WHAT IS THE IMPACT? As the ISO value increases, film’s sensitivity to light increases, allowing you to capture images at lower light levels and/or faster exposure times (that’s why ISO is also referred to as film speed). This is especially helpful for both low-light conditions and subjects with motion. FSTOP/APERTURE (MANUAL): 8.0 ISO SPEED (MANUAL): 50 SHUTTER SPEED (AUTO): 1/2 SECOND ISO 400 WHAT ABOUT QUALITY? The higher the ISO setting, the more grainy the image becomes. In the examples to the right, the digital camera’s minimum-supported ISO setting, a value of 50, resulted in a very long exposure requirement (1/2 second), but also resulted in a very smooth texture. The highest supported ISO value, 400, reduced the exposure time required by a factor of 10 (1/20 second), but resulted in a grainy overall texture. CAN I MAKE IT GRAINY? If your camera supports it, setting the ISO value to 400 or more will give you a grainy look that is typically associated with faster films. You can emulate this look by experimenting with Photoshop’s ADD NOISE filter under EFFECTS. FSTOP/APERTURE (MANUAL): 8.0 ISO SPEED (MANUAL): 400 SHUTTER SPEED (AUTO): 1 /20 SECOND Guide To Digital Photography © 2004 All rights reserved. 5 JPEG MEDIUM MEDIUM JPEG JPEG SMALL SMALL JPEG FILE SIZE: 0.4 MB IMAGES PER 64 MB CARD: 160 FILE SIZE: 0.9 MB IMAGES PER 64 MB CARD: 70 This image was saved from the camera with maximum JPEG compression. It looks ok until you see what you are missing. while subtle, there is clear loss of detail when working with jpeg originals. High levels of compression, as evidenced by the first two sets of JPEG images above, result in loss of detail and degradation in tone. These images are only suitable for use on the World Wide Web, where file size typically takes precedence over image quality and fidelity. SHOULD I USE JPEG OR 16-BIT RAW? WHY NOT ALWAYS WORK IN 16-BIT? There’s simply no question that you should capture your digital photography images in an uncompressed RAW format, if your camera supports it. This will have a significant impact on image quality, as demonstrated above. Many Photoshop features and filters only work on 8-bit-perchannel images. Photoshop 7.0 can only apply the following features to 16-bit images, typically for selection and correction: DUPLICATE, FEATHER, MODIFY, LEVELS, AUTO LEVELS, AUTO CONTRAST, AUTO COLOR, CURVES, COLOR BALANCE, HISTOGRAM, HUE HOW DO I OPEN IT? The new version of Adobe Photoshop, CS/8.0, can now open raw images directly, giving you complete control over a wide range of camera settings (meta data) during the conversion process. Alternatively, your camera’s manufacturer may supply software to browse, convert, and even correct images in RAW format. Note that the files are twice the size of standard 8-bit TIFFs. 6 Guide To Digital Photography © 2004 All rights reserved. /SATURATION, BRIGHTNESS/CONTRAST, EQUALIZE, INVERT, CHANNEL MIXER, GRADIENT MAP, IMAGE SIZE, CANVAS SIZE, TRANSFORM SELECTION, ROTATE CANVAS, MARQUEE, LASSO, CROP, MEASURE, ZOOM, HAND, HISTORY BRUSH, EYEDROPPER, SLICE, COLOR SAMPLER, CLONE STAMP, HEALING BRUSH, PATCH; PEN, SHAPE TOOLS (WHEN DRAWING WORK PATHS ONLY) AND A HANDFUL OF FILTERS. If you’ve upgraded to Photoshop CS, you have more tools that can edit a 16-bit image, but most filters still do not work in 16bit mode. SOURCE: ADOBE FILE FORMAT JPEG LARGE LARGE JPEG RAW 16-BIT 16-BIT RAW FILE SIZE: 1.5 MB IMAGES PER 64 MB CARD: 41 FILE SIZE: 3.3 MB IMAGES PER 64 MB CARD: 19 JPEG compression sacrifices fine detail and subtle tone shifts. Notice the difficulty the JPEG images have in maintaining the pattern of the El Camino’s grill. Other problematic areas are subtle tones, as evidenced by the shadow shifts from the car’s fender to hood. Even the best JPEG compression setting has loss of detail and tone. The RAW 16-bit format is THE uncompressed data captured by the camera’s CCD. Notice the detail in the grilL and the smooth transitions in the paint. The tone improvement is a result of the immense difference in gray levels per color: 256 (28) levels per color channel in a JPEG or other standard desktop file, vs. 65,536 (216) for the RAW format. WHY WORK IN 16-BIT? WHEN SHOULD YOU CONVERT TO 8-BIT? When applying a Levels or Curve correction on an 8-bit image, a smooth histogram (the range of tone from shadow thru highlight) can develop gaps, making it look like a comb. 256 levels of gray are barely enough to create a smooth gradation, as anyone working with desktop blends can attest. As the number of distinct levels are further reduced, visual banding occurs where you can see the steps as tones change, diminishing the overall quality of the image. These gaps create uneven gradation changes and introduce banding into your image. By applying Level and Curve corrections to a 16-bit image, you are working with over 65,000 levels of gray per channel, not just 256. That’s far more than needed to maintain a smooth blend or gradual tone change. During the creative process, you should only convert to 8-bit if you need to take advantage of an image editing feature that requires it. Even so, on a color-critical image you should perform all of your color correction and proofing adjustments (levels and curves, for example), as well as proof your image, before conversion. If you don’t need to apply a specialty filter, leave your images as 16-bit RGB until you are ready to print a proof or release your project. You can convert to CMYK while still in 16bit, and then finally convert to 8-bit right before collect-foroutput. Note that you will need to update the images, since the file will have been modified from the RGB. Guide To Digital Photography © 2004 All rights reserved. 7 How to Do Everything with Your Digital Camera! HOW TO DO EVERYTHING WITH YOUR DIGITAL CAMERA This book, How to Do Everything with Your Digital Camera, offers a comprehensive introduction to digital photography. The book’s author, Dave Johnson, is a photographer and a best-selling author of 15 books on portable technology and digital photography. This book divides the topic of digital photography into small, focused sections to help the novice to intermediate user gain practical insight into improving the quality of digital camera images. One of the book’s best features is its strong coverage of image composition topics. Johnson does a good job teaching the essential basics of what it really takes to make a good photo, in contrast to similar titles that often feature nothing more than a disjointed collection of tips and tricks. Image transfer is another topic that Johnson explains thoroughly. Topics include how to transfer photos to a PC, resolution options and different file formats for saving images, and understanding scanners and how to use them. Johnson also gives his recommendations on which types of scanners to buy. You will also pick-up a few tips on how to choose the image-editing program that is right for you. Johnson uses Jasc's PaintShop Pro to illustrate most of his image-manipulation examples. This program shares a lot of the same functionality as Photoshop, and you shouldn’t have trouble understanding the principles and applying them to your application of choice. This book provides a solid foundation in digital photography, hardware and software. It is a great choice for the studio or department that is expanding into digital photography.