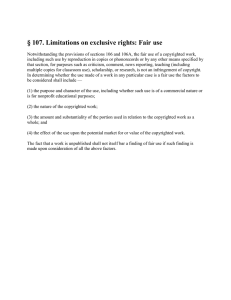

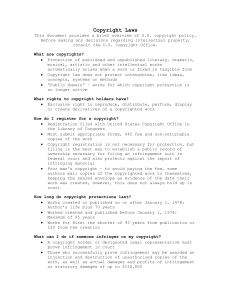

Campus Copyright Rights and Responsibilities

advertisement