The Consumer Lags Behind - American Institute for Economic

advertisement

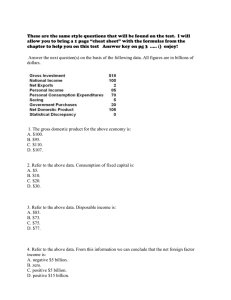

09|13 BUSINESS-CYCLE CONDITIONS The Consumer Lags Behind by Polina Vlasenko, PhD, Research Fellow Expansion continues, but stagnating personal incomes pose a threat to long-term growth. T sales, employment, and industrial production—continue to rise. The recovery does not benefit all parts of the economy equally. Business is gaining an outsized share of the growth, while households and individuals are not benefiting much. Overall, 91 percent of AIER’s he four-year-old economic expansion is likely to continue, according to the latest data reflected in AIER’s indicators of business-cycle conditions. While the pace of recovery may not be spectacular, all of the broad measures of aggregate economic activity—gross domestic product, THE INDICATORS AT A GLANCE Shaded bars represent official recessions. A score above 50 indicates expansion. PERCENTAGE OF AIER LEADERS EXPANDING 100 75 50 91 25 0 1985 PERCENTAGE OF AIER COINCIDERS EXPANDING 1988 1991 1994 1997 2000 2003 2006 2009 2012 100 75 50 100 25 0 1985 PERCENTAGE OF AIER LAGGERS EXPANDING 1988 1991 1994 1997 2000 2003 2006 2009 2012 100 75 50 100 25 0 1985 CYCLICAL SCORE OF AIER LEADERS 1988 1991 1994 1997 2000 2003 2006 2009 2012 100 75 50 90 25 0 1985 aier.org 1988 1991 1994 1997 2000 2003 2006 2009 2012 AMERICAN INSTITUTE FOR ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1 primary leading indicators are appraised as expanding (10 out of 11 indicators for which a trend is apparent) up from 82 last month. The cyclical score of leaders, which is based on a separate, mathematical analysis, has edged up to 90 from 88 last month. With both measures comfortably above 50, the leading indicators suggest that the recovery is likely to continue. STATISTICAL INDICATORS OF BUSINESS-CYCLE CHANGES Change in Base Data APR MAY JUN Cyclical Status JUL PRIMARY LEADING INDICATORS JUN JUL AUG + + - + M1 money supply (1) + + + + + + + Yield Curve Index (1) + + + ‑ ‑ + - Index of manufacturers’ prices (2) -? -? -? + + + New Orders for consumer goods (3) + + + + + + New Orders for core capital goods (4) + + + New housing permits (3) + + + + + + + Ratio of manufacturing and trade sales to inventories (3) -? -? + - + + Vendor Performance (2) +? ? ? + + - + Index of common stock prices (constant purchasing power) (2) + + + nc nc nc - Average workweek in manufacturing (3) + + + + - + + Initial claims for state unemployment insurance (inverted) (3) + + + ‑ ‑r + Change in consumer debt (4) + + +? PERCENTAGE EXPANDING CYCLICALLY 83 82 91 PRIMARY ROUGHLY COINCIDENT INDICATORS + + + + Nonagricultural employment (1) + + + - +r + + Index of industrial production (1) + + + + + - Personal income less transfer payments (1) + + + + + Manufacturing and trade sales (2) + + + + + + Civilian employment to population ratio (2) +? + + + + + Gross domestic product (quarterly) (1) + + + PERCENTAGE EXPANDING CYCLICALLY 100 100 100 Average duration of unemployment (inverted) (2) + + + Manufacturing and trade inventories (1) + + + + Commercial and industrial loans (1) + + + + PRIMARY LAGGING INDICATORS + - + + - + + - + + + Ratio of consumer debt to personal income (1) + + + + + + Change in labor cost per unit of output, manufacturing (2) + + + - - nc Composite of short-term interest rates (1) ? ? ? PERCENTAGE EXPANDING CYCLICALLY 100 100 100 nc nc No change. r Revised. U­ nder “Change in Base Data,” plus and minus signs indicate in­creases and decreases from the previous month or quarter; blank spaces indicate data not yet available. Under “Cyclical Status,” plus and minus signs indicate expansions or contractions; question marks indicate doubtful or indeterminate status. 2 BUSINESS-CYCLE CONDITIONS SEPTEMBER 2013 There are disparate trends for the sales of consumer products versus products purchased by businesses. AIER’s coincident and lagging indicators, all of which are appraised as expanding, with many reaching new highs, confirm that the economy has been growing for some time. The biggest change among the leading indicators this month is the substantial increase in the ratio of manufacturing and trade sales to inventories. A jump in manufacturing and trade sales, one of our coincident indicators, is responsible for the increase. In the 12 months to May, the latest month for which data are available, sales increased an inflation-adjusted 4.6 percent and reached the highest level in more than 50 years that the data had been collected. The level of sales surpassed the previous peak reached in October 2007, two months before the Great Recession started. But there are disparate trends for the sales of consumeroriented products versus products that are more likely to be purchased by businesses, with business taking the lead. This disparity is most visible in the sales of durable goods. Increases are concentrated in machinery, equipment, supplies and professional and commercial equipment. These products are likely to be purchased by businesses rather than people. Sales of durable consumer goods, such as appliances, furniture, and computers, are stagnating. The types of consumer goods that are posting sales increases tend to be nondurable necessities, such as groceries and fuel. One exception is the increase in sales of motor vehicles and parts, which are difficult to divide into purchases by businesses and purchases by people. All this adds up to a picture of an economy where businesses are doing fairly well, while consumers are focusing on meeting everyday needs. These trends are echoed in other indicators. New orders for core capital goods, a leading indicator, has been rising steadily for a year. Since July 2012, it has increased by 8.4 percent and currently stands only an inflation-adjusted 10 percent below its pre-recession value. In contrast, growth in new orders for consumer goods, also a leading indicator, has slowed. Over the past year, new orders for consumer goods rose only 3.3 percent and remain more than 15 percent below the pre-recession peak. The value of manufacturers’ shipments of consumer goods has been falling for four months and currently stands at about the same level it was in July 2012. The value of unfilled consumer Businesses are doing fairly well, while consumers are focusing on meeting everyday needs. aier.org MANUFACTURING AND TRADE INVENTORIES Manufacturing and (constant dollars, billions) Trade Inventories AN IMBALANCE EMERGES Business investment is brisk. Growth in consumer demand has slowed, with sales of durable consumer goods stagnating. 1600 800 Ratio of Manufacturing and RATIO OF MANUFACTURING AND TRADE Sales to Inventories SALESTrade TO INVENTORIES 400 NEW ORDERS FOR CONSUMER GOODS New Orders forbillions) Consumer (constant dollars, Goods 160 MANUFACTURING AND TRADE SALES Manufacturing and (constant dollars, billions) Trade Sales 80 NEW ORDERS New OrdersFOR for CORE CoreCAPITAL GOODS (constant dollars, billions) Capital Goods 1200 80 40 600 goods orders is close to the lowest level in more than 20 years. It has been stuck in the narrow range of $3.7-$4.4 billion ever since the recovery officially began in June 2009. (See Chart 1 on page 4.) When unfilled orders are high, it means that demand is growing faster than manufacturers can expand supply, and some orders go unfilled for a while. When unfilled orders are low, it means that demand is slack and manufacturers can easily fill almost all orders that come their way. That is what is happening now with consumer goods. Another sign of slack 20 in consumer demand is the accumulation of inventories. Manufacturers’ inventories of consumer goods (part of manufacturing and trade inventories) have risen close to the level they gained in early 2008, as the economy was about to go into a tailspin. The picture is different for the investment goods purchased by businesses. Demand for capital goods is sufficiently strong that the producers are falling behind on fulfilling orders. Inventories of core capital goods have been falling since last October. Unfilled orders have AMERICAN INSTITUTE FOR ECONOMIC RESEARCH 3 Chart 1. A Measure of Consumer Demand Hits a 20-Year Low Unfilled Orders for Consumer Goods, ($ billions, seasonally adjusted) 12 10 8 6 4 2 0 1992 1994 1997 2000 2002 2005 2008 2010 2013 Source: U.S. Census Bureau been rising since last December. They currently stand close to the pre-recession peak. The value of manufacturers’ shipments of core capital goods has been rising steadily since last September. A disparity in income growth mirrors the disparity in spending trends between businesses and people. Corporate profits after taxes have grown almost continuously since the end of the recession, interrupted only by a brief decline at the end of 2010. In the first two quarters of 2013, after-tax corporate profits rose only about 2 percent, but that comes on top of a spectacular A disparity of income mirrors the disparity in spending between businesses and people. 4 BUSINESS-CYCLE CONDITIONS 16 percent increase in 2012. Profits reflect the resources companies have available once all costs and taxes have been covered. Some of that money may be paid to shareholders as dividends. A lot of it is retained to finance business expansions or investments. With profits at healthy levels and growing, companies should have no difficulty financing investment spending, if they deem such spending desirable. People, however, are not faring as well as businesses. The rate of growth in real disposable personal income has been slowing for more than two years. Except for a 5.9 percent increase in income in December 2012 that reflected a one-time response to anticipated tax changes, growth of disposable income peaked early in 2011 at a 4 percent annual rate. It has been steadily falling since then. In June 2013, disposable SEPTEMBER 2013 Corporate profits have grown almost continuously since the end of the recession. personal income grew so slowly that, once adjusted for inflation, the purchasing power of that income was lower than the month before. The increase in July, the latest month of data, was just barely above zero. Overall, in the past 12 months, real disposable income increased only 0.8 percent. (Disposable income measures the money people have after taxes have been paid and transfers received.) Wages and salaries, a subset of personal income, show a similar pattern. Growth peaked in early 2011 at 5.8 percent and has been trending down since then. In 12 months to July, this category of income rose only 3.4 percent. Wages and salaries exclude types of income more likely to be received by the affluent, such as interest and dividends. As such, this subset of income better reflects the experience of most people. Since population grows over time, income per person is a measure that matters more to families than aggregate income. Per person income fared even worse than the aggregates would suggest. In the past 12 months, real disposable income per capita grew a meager 0.06 percent. Aggregate income is what supports aggregate economic activity. Since the recovery began a little over four years ago, real disposable personal income increased 5.9 percent. This contrasts sharply with the experience of the earlier business-cycle recoveries. Four years after the previous recovery, which began in November 2001, real disposable personal income had increased 12.4 percent. Following the recession that ended in March 1991, the increase was 12.8 percent. Following the deep recession that ended in November 1982, the increase was even larger, 18.5 percent. As a share of national income, compensation of employees has been falling since the end of the current recession. At the same time, corporate profits have been rising, both in total and as a share of national income. (See Chart 2 above.) What we see in the data are businesses investing in equipment and machinery at a fairly decent pace, but not expanding hiring or raising workers’ pay much. Every month this year, private employers added less than 200,000 workers to their payrolls, with a single exception of February, when 319,000 jobs were added. This is barely enough to absorb the population increase. The growth of average weekly earnings of production and nonsupervisory workers in the private sector has been stuck below a 2 percent annual rate for the past 12 months. Such a slow pace of earnings Growth in real disposable personal income has been slowing for more than two years. aier.org 67% Chart 2. Corporations Flourish, Compensation Lags Shares of National Income 14% 66% 12% 65% 10% 64% 8% 63% 62% 6% 61% 4% Compensation of employees, left scale Corporate profit after tax, right scale 60% 2% 59% 58% 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, National Income and Product Accounts growth was seen only a handful of times in the 50 years that the data were collected—in 2009, at the end of the most recent recession, in late-2003, in late-1995, and in 1986. Each of these episodes was accompanied by a slowing of GDP growth to below a 3 percent annual rate, sometimes far below. All this leaves people with stagnating incomes, which explains the pattern of consumer purchases. The demand for nondurable necessities, such as groceries, grows reasonably well, but the demand for most things people can do without, such as appliances and computers, is slacking. The economy’s engine is running unevenly, posing a potential danger to sustained growth. Business spending and the everyday spending by consumers have been enough so far to pull the recovery along. But consumer durable goods industries, which are more cyclically sensitive, The economy’s engine is running unevenly, posing a danger to sustained growth. seem to be running out of steam. Without an improvement in people’s incomes, the situation is not likely to change. People may have increased their spending as far as their incomes would allow. This year, the personal saving rate has fallen to an average of 4.3 percent of disposable income, down from more than 5.5 percent in each of the previous three years. The saving rate today is higher than it was during the credit-happy years leading up to the recession. In 2005-2007, it hovered around 3 percent. But given that today banks are much less willing to lend than they were during the boom, we would not AMERICAN INSTITUTE FOR ECONOMIC RESEARCH 5 0% expect, nor would we want, the saving rate to fall much further. Without an unhealthy expansion of borrowing, people will only be able to increase demand for consumer goods when they see their incomes grow. Businesses, with healthy profits and cash reserves, 6 BUSINESS-CYCLE CONDITIONS can continue spending. Ultimately, however, the only reason businesses spend is because they expect consumer demand to grow. Anticipation of future consumer demand has to justify continued business investment. If growth of consumer demand does not materialize, businesses will be SEPTEMBER 2013 quick to cut back on spending. Consumer spending accounts for a much bigger part of the overall economy than does business spending, Unless its growth accelerates, GDP is unlikely to grow much faster than it has been. Businesses cannot be the sole driver of economic growth for long. n APPENDIX. PRIMARY LEADING INDICATORS 2000 Ratio of Manufacturing and Trade Sales to Inventories (3) M1 Money Supply (1) (constant dollars, billions) 1.0 0.9 1000 0.8 0.7 500 800 0.6 Yield Curve Index (1) (cumulative total) Vendor Performance: Slower Deliveries Diffusion Index (2) (%) 80 600 60 400 40 200 20 0 100 100 0 Index of Manufacturers' Supply Prices (2) (percent) Index of Common Stock Prices (2) (constant purchasing power) 880 75 440 50 220 25 110 0 55 Average Workweek in Manufacturing (3) (hours) 160 New Orders for Consumer Goods (3) (constant dollars, billions) 46 44 80 42 40 40 38 20 80 New Orders for Core Capital Goods (4) (constant dollars, billions) Initial Claims for Unemployment Insurance (3) (1000s, inverted) 160 260 40 360 460 20 560 660 10 2800 New Housing Permits (3) (thousands) 3-Month Percent Change in Consumer Debt (4) 12 10 8 6 4 2 0 -2 -4 1400 700 350 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 Notes: 1) Shaded areas indicate recessions as dated by the National Bureau of Economic Research. 2) The number in parentheses next to the name of a series is an estimate of the minimum number of months over which cyclical movements of a series are greater than irregular fluctuations. That number is the span of each series’ moving aver­age, or MCD (months for cyclical dominance), used to smooth out irregular fluctuations. The data plotted in the charts are those MCDs and not the base data. aier.org AMERICAN INSTITUTE FOR ECONOMIC RESEARCH 7 APPENDIX. PRIMARY ROUGHLY COINCIDENT INDICATORS 256 Nonagricultural Employment (1) (millions) Manufacturing and Trade Sales (2) (constant dollars, billions) 1200 128 600 64 300 32 150 128 Index of Industrial Production (1) (2007 = 100) Civilian Employment as a % of the Working-Age Population (2) 66 64 63 32 60 16 57 8 54 12800 Personal Income Less Transfer Payments (1) (constant $, billions) Gross Domestic Product (1) (quarterly, constant dollars, billions) 20000 10000 6400 5000 3200 2500 1250 1600 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 APPENDIX. PRIMARY LAGGING INDICATORS 5 Average Duration of Unemployment (2) (weeks, inverted) Ratio of Consumer Debt to Personal Income (1) (percent) 23 15 18 25 13 35 8 45 3 1600 Manufacturing and Trade Inventories (1) (constant dollars, billions) % Chg. from a Year Earlier in Mfg. Labor Cost per Unit of Output (2) 16 12 8 800 400 4 0 -4 200 -8 -12 1600 Commercial and Industrial Loans (1) (constant dollars, billions) Composite of Short-Term Interest Rates (1) (percent) 18 15 800 12 400 9 200 6 100 3 50 0 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 1950 1960 1970 1980 Business-Cycle Conditions is published by American Institute for Economic Research, a nonprofit, scientific, educational, and charitable or­ganization. 8 BUSINESS-CYCLE CONDITIONS SEPTEMBER 2013 To contact AIER by mail, write to: American Institute for Economic Research PO Box 1000 Great Barrington, MA 01230 1990 2000 2010 Find us on: Facebook: facebook.com/ AmericanInstituteForEconomicResearch Twitter: twitter.com/aier LinkedIn: linkedin.com/company/americaninstitute-for-economic-research For more information or to donate, visit: www.aier.org