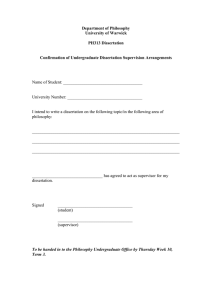

Developing and enhancing undergraduate final

advertisement