sao paulo case study overview

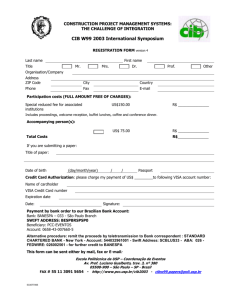

advertisement