Some Reflections on Copyright Management Systems and Laws

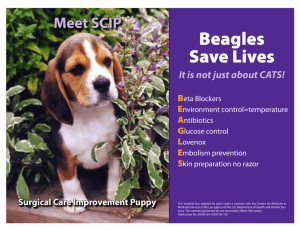

advertisement