Donee organisations — clarifying when funds are

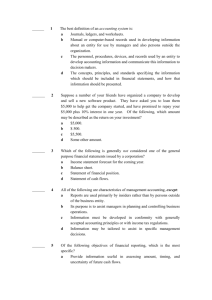

advertisement