How to Nominate an Individual Building, Structure, Site or Object to

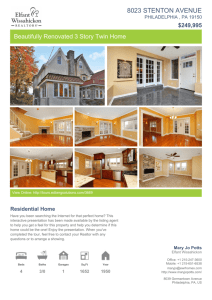

advertisement