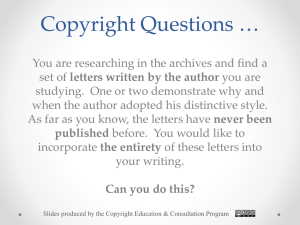

Consultation Practices within Scottish Local Authorities and

advertisement