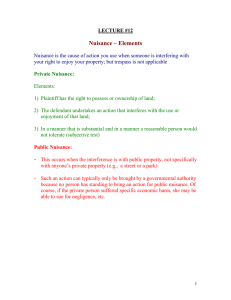

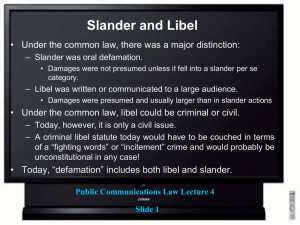

The Art of Insinuation: Defamation by Implication

advertisement