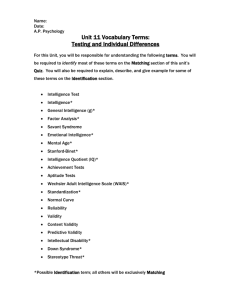

Why g Matters: The Complexity of Everyday Life

advertisement